Hi all, hope everyone is keeping well. Today, I want to just focus on the Welsh princess buried in London, a woman you have likely not heard about.

Nestled up a nondescript alleyway in the heart of London’s financial district, opposite Cannon Street station in one of the busiest areas in the world during the working week, lies a modest but appealing 10-foot monument, crafted out of Welsh bluestone. This was unveiled in 2001, designed by Nic Stradlyn-John and sculpted by Richard Renshaw, and represents an artistic depiction of a mother protecting her children during time of war.

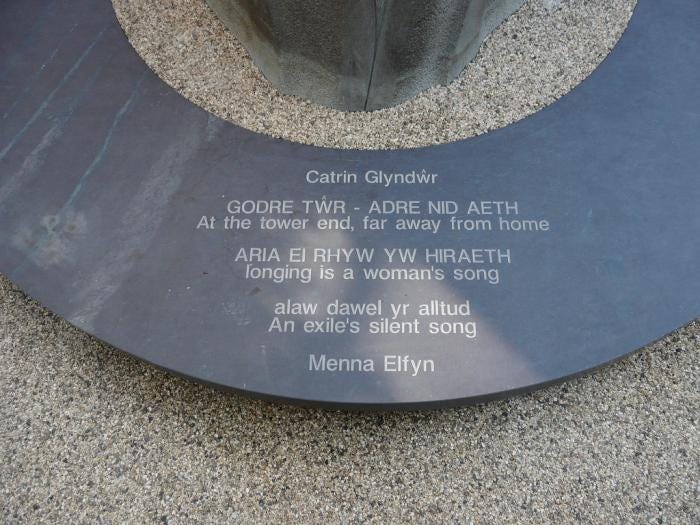

At the base lies a stone inscribed with a Menna Elfyn poem called ‘an exile’s silent song’, which reads:

‘Godre twr adre nid aeth,

Aria ei rhyw yw hiraeth’

‘At the tower end –far away from home.

Longing is a woman’s song’

This is the memorial dedicated to Catrin ferch Owain Glyn Dŵr. Catrin (a Welsh variant of Catherine) was one of the daughters of Owain Glyn Dŵr, the defiant Welsh nobleman who in 1400 led a national uprising against English rule. If we discount Henry VII, Owain was the last native Welshman to hold the title Prince of Wales, which he adopted at the outset of his revolt. Catrin’s mother was Margaret Hanmer, daughter of an English chief justice named Sir David Hanmer. Margaret was praised in verse by the poet Iolo Goch, who regarded her ‘the best of wives’ who mothered ‘a beautiful nest of chieftains’.

It is not within the scope of this article to cover Glyn Dŵr’s war, but I do cover it in detail in my book Son of Prophecy, – Glyn Dŵr’s first cousins, indeed his closest supporters, were the Tudur brothers of Anglesey, including Maredudd ap Tudur, the great-grandfather of Henry VII.

Nevertheless, in 1402, Glyn Dŵr secured a significant coup when Edmund Mortimer, an English nobleman who he had captured in battle, grew irritated by Henry IV’s reluctance to ransom him, and elected to defect to the rebels’ side. Through his mother, Mortimer was a great-grandson of Edward III and uncle to the young Earl of March, who some considered as having the greatest claim to the English throne. To bond themselves together further, on 30 November 1402 Mortimer took Catrin’s hand in marriage. We can, then, reasonably claim she was at least fourteen years at this juncture.

Glyn Dŵr’s peak came in 1404, when he was able to host a Welsh parliament in Machynlleth. This was also the year he assumed residence in the English-built fortress of Harlech, on the north-west Welsh coast. This, in many respects, became his administrative, political, and military seat, not to mention his family home. Glyn Dŵr’s ancestral seat of Sycarth, where Catrin had likely been brought up, had been razed to the ground by the English forces of Prince Henry, the future Henry V, the previous year.

In February 1405, meanwhile, Glyn Dŵr, the rebel Percy earl of Northumberland, and Catrin’s husband Mortimer agreed a remarkable compromise known as the Tripartite Indenture, that laid out the division of England and Wales between the three men in the event they knocked the House of Lancaster off their throne. If realised, Catrin’s in-laws would preside over the whole of southern England, including London.

The rebels, however, were already on the wane and under increasing military pressure. By 1408, Harlech was under bombardment with cannon, which must have been terrifying for Catrin and others cooped up within. In the previous years, she had become a mother, having one son named Lionel after his paternal ancestor Lionel of Antwerp, and three daughters. We do not know the circumstances, but during this siege, Edmund Mortimer died, their son Lionel had died, and Catrin was left bereaved and probably scared for her future.

Sieges are horrific for those trapped within the castle, as supplies gradually run out. Men, women and children die of starvation in heavy numbers, if not from collapsing masonry or walls caused by siege engines. We know from other 15th century sieges that many were forced to subsist on cat, rat or dog meat. When Harlech finally capitulated in February 1409, one can only wonder on Catrin’s mind state.

As a daughter of Welsh royalty, Catrin was taken into English royal custody, together with her mother Margaret Hanmer, a sister, and her surviving daughters. Adam of Usk, a contemporary chronicler, notes:

‘the wife of Owen, together with his two daughters and three granddaughters, daughters of sir Edmund Mortimer, and all household goods, was taken captive, and sent to London unto the king’

Their new home was to be another fortress, this time the Tower of London. This is an implicit recognition of her importance as a political prisoner, but also had practical incentive from an English perspective – to not allow Glyn Dŵr’s blood to be free to foment future rebellion. When the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd had been conquered in 1282, the only daughter of Llywelyn the Last, Princess Gwenllian, was confined to a priory in Lincolnshire and died childless.

In fact, another prisoner at the Tower was her brother Gruffydd ap Owain, though he appears to have died around 1412. Her father had escaped into the wilds of Snowdonia, and his whereabouts are unknown even today. Another brother, Maredudd ap Owain, eventually accepted a pardon in 1421 before he too drifted into obscurity. A sister named Alys was married to a prominent Herefordshire sheriff named John Scuadmore and emerged unscathed by the rebellion, whilst little is known about other siblings like Madog, Thomas and John.

Catrin did not outlive her brother Gruffydd for long. Within a year, she too was dead, and so too were her daughters. We know no further information, nor what became of her mother. Was it a natural death, or were suspicious circumstances at play? The only evidence of her death occurs in the Exchequer records of 1413, reading: ‘for expenses and other charges incurred for the burial of the wife of Edmund Mortimer and her daughters, buried within St Swithin's Church London - £1’.

Unfortunately, the medieval church at St Swithin’s was destroyed during the Great Fire in 1666, and Catrin’s final resting place has now been lost. The churchyard has been redeveloped into a public garden, and it is here her memorial now stands, marking the only known resting place of the Glyn Dŵr family, who strove high but fell sharply. If you are ever around Cannon Street in London, do pop along and take a moment to remember Catrin of Wales.

Subscribe

If you have enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (completely free!) to receive future posts directly to your inbox. This will include historical snippets, book news and extracts, event details and also some insight into the world of the historical author.

If you’ve already subscribed, you are awesome and Vera says MIAOW with her paw raised in respect.

Wow what an incredible and sad story. I knew Edward Mortimer became Glyn Dwr's son in law, but nothing about his wife and family. Such a brave lady. Such a tragic end. Thank you.😢

Thank you for sharing the story of this brave and tragic woman. I had never come across her before but she seems to have gone through so much, even in such a short life.