On 28 January 1457, far from the centres of English power, a baby was born in West Wales who would one wear the crown of England. That boy’s name was Henry, the first of the Tudors to reign.

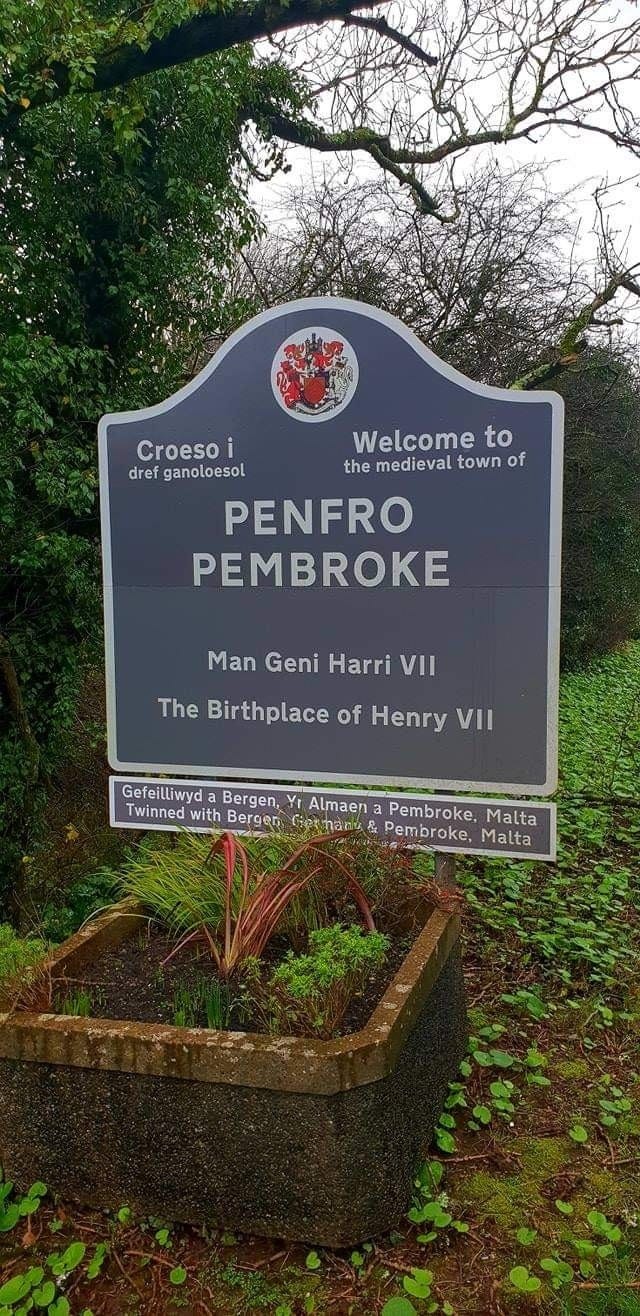

Henry is fondly remembered in his hometown of Pembroke, where his presence is keenly felt today – his birth is recalled upon the signs in and out of the town, there is a local cider named for him, you can sit upon a bench bearing his name, see some Victorian stained glass celebrating him, the school is named after him, and of course, there is a gleaming statue that proudly stands on the quay in the shadow of his birthplace, the towering fortress that ranks alongside the very greatest on the island.

What follows is an adapted extract taken from my Tudor family biography, ‘Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor’, available worldwide NOW!

Extract from ‘Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor’

When Jasper Tudor received news of his brother Edmund’s death, he embraced his brotherly duty at once, springing into action to safeguard his young sister-in-law, Margaret Beaufort. Carrying Edmund’s child in her womb, under Jasper’s direction the now dowager countess was brought from Lamphey to his imposing baronial seat of Pembroke, an uncomfortable but mercifully short journey of just a couple of miles. She was likely incapable of travelling further.

On 28 January 1457, just under three months since Edmund’s death, Margaret gave birth to their son in a darkened chamber specially prepared for the purpose. It had not been an easy delivery, and Margaret’s underdeveloped body, still just thirteen years old, struggled with the strain of childbirth so that for some time her life was thought to be in danger.

In a sermon delivered forty years later, her confessor Bishop John Fisher (one day to be put to death by her grandson Henry VIII) recounted that though the child was ‘wonderfully born’, it ‘seemed a miracle that at that age, and of so little a personage, anyone should be born at all’. It is probable the traumatic effects of labour so young caused Margaret lasting harm, as despite two later marriages she would never conceive a child again. It is particularly telling, poignant even, that many years later Margaret protested plans to marry her namesake granddaughter to the king of Scotland when just nine years old, compassionately drawing on her own harrowing experience to protect the young princess’s wellbeing.

According to the poet and antiquarian John Leland, writing between 1536 and 1539, Margaret’s child was born in a thirteenth-century guard’s chamber that formed part of the outer bailey’s defensive wall. During a visit, Leland claimed to have been shown a chimney that bore the arms and badges of the first Tudor king, but though he may very well have been reporting a local tradition, the claim seems to be dubious. Today, this is known as the Henry VII Tower and features a quaint waxwork of the nativity scene.

Despite her tender age, Margaret was a noblewoman of a great and royal lineage, her baby a close relative of the king on both sides of his family tree. In consideration of her ancestry, station, and most of all her physical condition, Margaret likely gave birth in the more comfortable domestic quarters reserved for the use of the lord, her brother-in-law Jasper, or other honoured guests.

Recent excavations have revealed the stone foundations of such a building in the outer bailey of the castle, away from the more bustling environs of the inner ward, where the Great Hall, chapel, chancery and dungeon were in heavy daily. A private dwelling of high status fitted with the latest amenities, such a noble suite was a far more appropriate environment for Margaret’s labour than a guard’s chamber near the gatehouse.

Another sixteenth-century tradition, recounted by Elis Gruffudd who claims to have heard the story from his elders, suggests the boy was originally named Owain, the name of his grandfather. This, however, was likely influenced by knowledge of the Tudor accession to the English throne and the then-current assertions of the Welsh bards that the ancient prophecies foretelling of a Welsh national deliverer had been fulfilled. In these prophecies, the hero was often named Owain. In the absence of a father, the reality is that Margaret had almost certainly named her son as intended, bestowing upon him the name Henry in honour of her cousin, Henry VI. It will also be noted the king was the boy’s half-cousin on his Tudor side, an appropriate and respectful name in every sense, however romantic the claim of Elis Gruffudd.

The enduring bond between mother and child, a connection that would prove unshakable across the course of their turbulent lives, was one forged by their first few moments together inside the whitewashed stone walls of Pembroke, where Margaret ‘wisely attended’ to her son’s care. She was, in truth, still a child herself – a mother and a widow at just thirteen years old, and after a terrible ordeal may have just been able to summon the strength to look into her baby’s small blue eyes and feel relief. She, like the son she now held, had also never known her father, who had died when she was just one years old. In letters exchanged between the pair in later life, to Margaret, Henry was ‘all my worldly joy’ and ‘only beloved son’. In turn, he would respond noting his appreciation for ‘the great and singular motherly love and affection’ his ‘most loving mother’ had always shown him. Though they spent most of their life up to the point he became king at 28 apart, they were firmly bonded.

After surviving the harrowing experience of childbirth, Margaret continued to convalesce at Pembroke, supported by a compassionate and experienced local network of midwives, wet nurses, and mothers. One of those nurses was a Welshwoman named Joan, wife of Philip ap Howell, later rewarded by Henry when king with an annuity of twenty marks for her services. Together, this collection of aides tended to Margaret’s painful physical needs whilst assuaging any concerns she had about her son’s welfare. Once her strength had recovered sufficiently to be reintroduced to society, she was delicately escorted to the porch of a nearby church, probably the nearby thirteenth-century St Mary’s, to experience an important ceremonial ritual known as churching. This was a religious practice intended to restore purity after the birthing process.

From his very first breath, young Henry joined the noble ranks, inheriting his father’s title as earl of Richmond. History would remember this boy as Henry Tudor, though by the practice of the day in which he lived he was properly known from birth as Henry of Richmond (or in Welsh, Harri ap Edmwnd ap Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur!). The course of an internecine war played out on battlefields across England and Wales would, in time, cost Henry his earldom and his freedom, a boy forced to navigate unsteadily through a frightening adolescence of hardship and danger whilst exiled for more than a decade, separated from his mother’s embrace and his homeland. He would, against every odd imaginable, emerge as the unlikeliest candidate ever proposed for the English throne.

Back in the cold winter of January 1457, however, a helpless babe in the arms of a mother not that much older than him, the birth of this remarkable survivor that would one day don a crown passed with little comment from contemporaries. Just another noble mouth to feed in a nation distracted by inward conflict, nobody outside his immediate family and their household paid any attention to the arrival of Henry Tudor.

Son of Prophecy

'Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor' is a 300-year history of one Welsh family, and how they emerged from the wilds of Gwynedd, navigated the murky and violent waters of Welsh-Anglo politics, and eventually found their way, almost improbably, onto the English throne. This story involves war, treason, escapes and love.

Fourteen years in the making, from defiant Welsh rebels to unlikely English kings, this is the story of the Tudors, but not how you know it. A BBC History Magazine 2024 Book of the Year, it is available to buy worldwide now HERE

Poor Margaret! Would I be wrong to think that Edmund might have restrained himself, even in those days? Horrific. On the bright side: I'm in the US and very much looking forward to reading your book over the next week or so.

A widow and mother at thirteen?! At thirteen, I couldn’t manage to floss between my braces successfully…