Croeso (or Welcome), to another edition of ‘A Chronicle of Dragons & Cats’, and thank you for reading! If you have already subscribed, diolch yn fawr for coming along on this journey and I hope you’re enjoying. Any likes, comments and shares are always appreciated. It’s not easy getting history out to the masses at the moment!

If you haven’t subscribed yet, please take a look through the newsletter using the handy navigation tabs at the top of the homepage and if you like what you see and want more, then click the subscribe button below. Each post is then sent out directly to your email and it’s FREE!

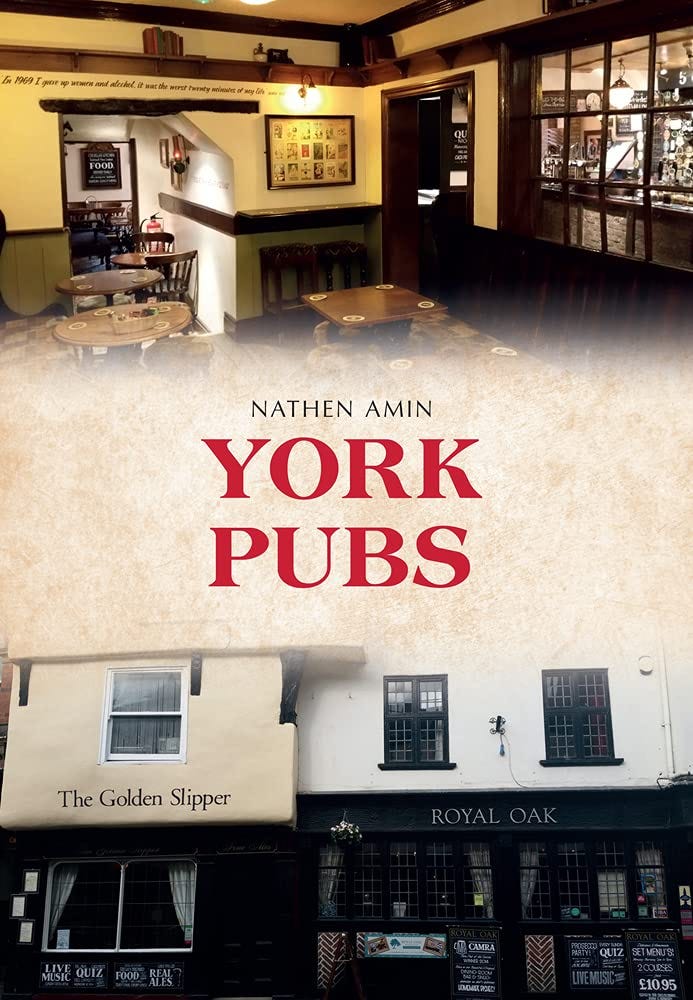

Back in 2016, I released my second book which was titled simply ‘York Pubs’. I mean, that tells you everything the book was about - it was about Pubs in York. I had free reign to pick whatever pubs I wanted and choose to only focus on those with a significant historical footprint in the city, locations which had been a pub for a lengthy amount of time rather than old buildings which had recently been converted into pubs.

The earliest reference to the pub industry in York can be found in the thirteenth century Roll of Freemen. This fascinating document provides various references to publicans, with William de Castelford, Adam de Pontefract, Rogerus de Wambewell, William de Whityngton and Johannes de Appelby listed as ‘taverners’ in 1277. The first known record of a specific pub in York is that of the George, which was documented in a 1455 will as Hospicium Georgii.

The Bull is mentioned a few years later when a Corporation Ordinance dated 27 April 1459 decreed that ‘no aliens coming from foreign parts shall be lodged within the said city, liberties, or suburbs thereof, but only in the Inn of the Mayor and Commonalty, at the sign of the Bull in Conyng Street’. This regulation commanded that all visitors to the city not native to England were only to stay at the Bull, which stood on one of the city’s main thoroughfares, Coney Street. Other references to fifteenth century pubs include the Crowned Lion (1483), the Dragon (1484), the Boar (1485) and the Swan (1487).

The sixteenth century witnessed a growth in licensed premises, which brought an upsurge of legislature by authorities concerned with a rise in drunken disorder. In 1550 there were nine inn-holders recorded in York; by 1596 this had grown to sixty-four along with 103 alehouse keepers. Parliament in London attempted to control this public disorder with the Ale-Houses Act 1551, passed to control the ‘abuses and disorders as are had and used in common ale-houses’. Justices of the Peace were empowered to ‘remove, discharge and put away common selling of ale and beer in the said common ale-houses’ in locations they considered such sanctions were necessary.

Following from Parliament’s attempts to regulate the industry and to prevent continuing disorder, on 23 April 1562 139 inn-holders and brewers were officially granted licences by the Corporation of York and the Lord Mayor to continue brewing ale. A decade later the Council of the North, which represented Queen Elizabeth in the region, demanded stricter enforcement of the alehouses, suggesting licensing had not curbed any widespread issues. A further act in 1604 attempted to clarify the usage of drinking houses to be for the ‘Receit, Relief and Lodging of Wayfaring People travelling from Place to Place’ and not for ‘Entertainment and Harbouring of lewd and idle People to spend and consume their Time in lewd and drunken Manner’.

By 1663 it was recorded that York had licensed 263 public houses, whilst by 1700 it was reported that there was one drinking establishment for every thirty-nine people. And as any visitor to the modern city will attest, it feels like its hardly declined ever since.

So, which one is my favourite? There are many I deeply love, having lived in York for eight years, and, of course, having researched them for this book. But there was one which combined my love for historic pubs and Henry VII.

The Phoenix

The Phoenix on George Street is situated in close proximity to Fishergate Bar and is the last surviving pub within the city walls which once served the old cattle market. A pub probably operated on this site in the late eighteenth century and it would have benefited from the busy trade which took place at the nearby market.

Now Fishergate Bar with its round-headed arch in itself has a very interesting history. This is one of the six gateways in the city walls, guarding entrance towards the south of the city. We know it was built before 1315, though the current gateway and sixty yards of the wall were rebuilt in 1487 on the orders of Sir William Tod, mayor of York. An inscription above the arch details this event.

This year was significant in York’s history due to the Lambert Simnel affair, a revolt raised against Henry VII which sought to put the Yorkist prince, Edward of Warwick, on the English throne. The largely Irish and German rebel army were marching through Yorkshire trying to galvanise support, and a detachment headed for York to rouse the city.

On 6 June 1487, the York City council met in Guildhall and decided ‘they would keep this city with their bodies and goods to the uttermost of their powers’ on behalf of Henry VII. Wardens were placed along the walls to keep watch and everyone was barred from leaving the city. It is likely Mayor Tod had had Fishergate Bar and the walls strengthened in advance of this through the urging of his king.

Two of the rebels, the Yorkshire barons Scrope of Masham and Scrope of Bolton brought their armies to Bootham Bar on 12 June, declaring their support for ‘King Edward’ before attacking the gateway. The York guards, however, ‘manly defended’ their city - afterwards, Mayor Tod issued a proclamation reiterating York’s loyalty to Henry VII.

Two years later, however, Fishergate Bar would be heavily damaged during a tax revolt led by local peasants against Henry VII. The king was seeking money to help defend his ally Brittany in their war against France, but perhaps reasonably, already burdened folk in Yorkshire didn’t see why they should pay for something that didn’t directly affect them. When Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, tried to collect these taxes in April 1489, he was ambushed and murdered. Some speculate this was because Percy had failed to support Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth four years earlier.

In the process, Fishergate Bar was torched, before the revolt was suppressed and the ringleader, John à Chambre, was hanged. The taxes were forgotten about. The gateway, however, damaged sufficiently that the arch was bricked up - when he visited the city in 1536, John Leland noted simply ‘Fishergate stopped up since the communes burned it in the time of Henry VII’. The gateway would remain closed until 1827 when it was finally reopened to give better access to the cattle market. Steps up to the city walls were also added at this time. You can still see the slot where the gate once had a portcullis, and some of the stonework is discoloured by fire, said to be from the 1489 attack.

Back to the pub; during the early nineteenth century, this was called the Labour in Vain, and in 1839 was run by Ann Jolly. I found this out by searching through the Street Directories, cross-referencing with the Newspaper Archive and Census records. Ann’s deceased vessel-owner husband John Jolly had previously owned a pub on King’s Staith also called the Labour in Vain and it seems likely Ann retained the name when she moved to George Street.

The name and associated imagery may be considered controversial in the present era but during the early Victorian era was prevalent across the country. Although the name seems innocuous at first, it was often accompanied with a pub sign which depicted a woman scrubbing a black child with the slogan ‘you may wash him and scrub him from morning to night, your labour’s in vain, black will never come white’.

Ann Jolly retained control for over fifteen years until her death in 1854 aged 67. She was buried in the nearby St George’s Courtyard. By 1858 the new landlady was Caroline Pemberton along with her son John and daughter Jane. The pub had acquired the informal name of the Black Boy by this period, alluding to the pub sign. In 1867 the pub was renamed the Phoenix with William Sawyer the new publican. It has been theorised that the new name was adapted from the nearby Phoenix Iron Foundry. Over the next three decades the pub underwent a succession of short term landlords, including Joseph Smith in 1872, Benjamin Stephenson in 1876, James Renwick in 1881 and William Blakely in 1889. By 1893 Thomas Page had taken over before John Atherley became licensee in 1896.

As well as John, the Atherley family comprised of his wife Annie and adult children Beatrice and Ernest who worked in the pub, which in 1902 consisted of two smoke rooms and a serving bar. Although later renovations have taken place the pub still retains its basic internal outlay from a 1897 renovation by John Smiths Brewery. The bar room contains a large etched glass window bearing the pub’s name with a serving hatch in the lobby providing access to the bar.

Today, it is an independently run pub, a real working, living, authentically historic premises, and is worthy the short walk from the city centre to explore, or taking a brief moment off the walls for refreshment. When I look upon the pub from outside Fishergate Bar, I get a wonderful feeling wash over me, as two of my interests combine before my eyes - the reign of Henry VII and historic pubs!

As always a great read. York, one of my favourite cities and a must go to whenever I am in England. My must go to visits are to Warwick, York, Carlisle ( I used to live in Stanwix as a child) Durham, Hexham. Obviously Scotland and Wales are on my itinerary too but I’m talking about England. If there is any group of Islands that are of interest to historians or lovers of outstanding scenic beauty, the British Isles are matchless, in my opinion anyway.

I worked as a newspaper reporter in York in the 1970s. In that role I became very familiar with several of York's multitude of pubs. Nice article ... and Cheers!