The Welsh Martyr of Llandovery

The brutal execution of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Fychan, watched by the future Henry V of England.

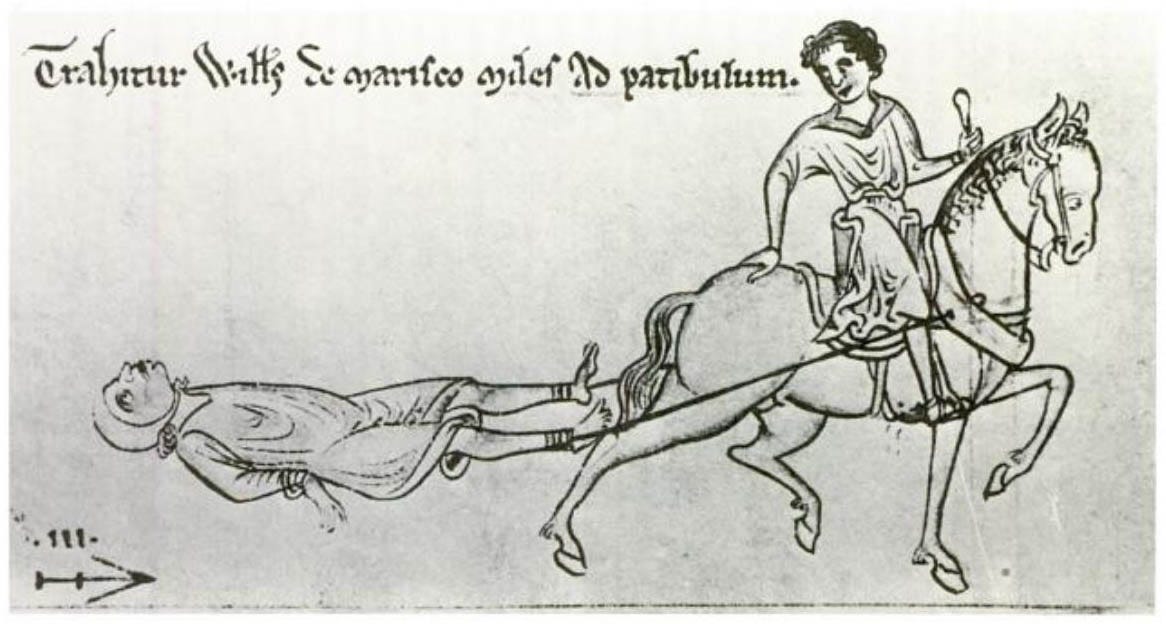

On 9 October 1401, a Carmarthenshire landowner named Llywelyn ap Gruffydd Fychan of Caio was executed in Llandovery marketplace. In front of the watching King Henry IV of England and his fifteen-year-old son Prince Henry (the future Henry V, he of Agincourt-fame), he was hanged until near death, cut down, his genitals were removed, he was disembowelled whilst alive, his entrails burned in front of him, beheaded, and his corpse was cut into four pieces, to be sent to various towns as a gruesome warning the fate of traitors.

Regarded approvingly by the contemporary chronicler Adam of Usk as ‘a man of gentle birth and bountiful, who yearly used sixteen tuns of wine in his household’ (that is hundreds of bottles a week!) Llywelyn’s crime was being ‘well disposed’ to the man he recognised as his Prince of Wales – not the English-born prince who formally held the title, Prince Henry, but Owain Glyn Dŵr, the Welshman who laid claim to the title the previous year.

When Glyn Dŵr raised the flag of revolt in September 1400, many Welshmen picked up their weapons and went to work, including Glyn Dŵr’s first cousins, the Anglesey sons of Tudor (read more about this entire episode of history in my book ‘Son of Prophecy’, more info below). Across the next year, many English communities in in north Wales were torched, the great Conwy Castle was captured, the Welsh won victory in battle at Mynydd Hyddgen, and when the rebellion threatened to engulf the south, this provoked a largescale royal expedition to be mustered in the autumn of 1401.

Led by Henry IV, the intention was to suppress the revolt, or war of independence depending on one’s perspective, and capture the Welshman who had captured the hearts of his countrymen. The English king invaded through central Wales ‘with a strong power’ according to Adam of Usk, heading westwards into Powys from Shrewsbury and Hereford. Along the way, Adam reported the English ravaged mid-Wales ‘with fire, famine and sword…not even sparing children or churches, nor the monastery of Strata Florida’. Glyn Dŵr’s men, however, ‘lurking in the mountains and wooded parts’, embarked on guerrilla warfare, inflicting ‘no small hurt to the English, slaying many of them, and carrying off the arms, horses, and tens of the king’s eldest son, the Prince of Wales’. In short, Glyn Dŵr proved himself a dangerous nuisance and could not be drawn into the open.

The king’s search brought him eventually to Llandovery, an important market town in the heart of Carmarthenshire, something of a strategic gateway to the south and west. It was here, according to local tradition that frustratingly cannot be substantiated, that Llywelyn ap Gruffydd entered the picture, leading the English royal army on a wild goose chase around the local countryside, allowing Glyn Dŵr, who was in the area, to slip away undetected.

A later suggestion by Lewys Dwnn, recording Welsh genealogy in the 16th century, suggests Llywelyn’s wife was Sioned, a daughter of the Scudamore family of Kentchurch in Shropshire. This may be significant in explaining Llywelyn’s reluctance to betray Glyn Dŵr, as the latter’s daughter Alys was also married to a Kentchurch Scudamore. Family as well as political connections, perhaps.

By whatever manner he incurred the wrath of the English king, Llywelyn would pay dearly. Judged guilty of committing High Treason, that is disloyalty to the crown, the punishment was grim, as outlined in the Treason Act of 1351, which condemned men judged to have planned the death of the king, to have levied war upon him, or to have given aid to his enemies.

According to Adam of Usk, on the Feast of St Denis, Llywelyn nevertheless ‘willingly preferred death to treachery’, and this is what he received, his body being torn to shreds before a watching crowd, including, one imagines, his wife, children, and friends. Though he died a traitor in the eyes of the English crown, it is likely Llywelyn viewed himself anything but, since he did not recognise that crown’s authority.

Sadly, not much is known of this shadowy figure who was executed for his loyalty, other than his name, the manner of his agonisingly drawn out death, and his considerable alcohol consumption. His son Rhys would fight as a man-at-arms on the famous Agincourt campaign of Henry V, the former Prince of Wales who had probably watched Llywelyn’s final moments.

His legacy, however, endures. Considered by some a Welsh martyr willing to die for his cause, in 2001 Llywelyn was honoured with a 16-foot-tall stainless steel statue bearing a shield with Glyn Dŵr’s arms. The statue, depicting a figure with an empty helmet and cloak, was said by its sculptor to represent the a “brave nobody”. Today, it still overlooks where this “nobody”, loyal to his end, took his last breath in front of a king.

Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor

I cover the Glyn Dŵr uprising and the part played by his cousins, the sons of Tudor, in my book ‘Son of Prophecy: The Rise Henry Tudor’. Fourteen years in the making, from defiant Welsh rebels to unlikely English kings, this is the story of the Tudors, but not how you know it.

No matter where you are based in the world, Blackwells Books ships FREE OF CHARGE worldwide (yes, you lot in America can get it NOW).

Order BY CLICKING HERE

Regarding the young Henry v, reading Dan Jones he certainly was a tough nut.

He had a Welsh garrison hung, watched 3 heretics being roasted and he was at the death of Lord Cobham. From what I recall, Lord Cobham was a supporter of the Lollards, one of their leaders, his death was very brutal. He was hanged in chains over a fire and literally burned and slowly roasted to death. This same Prince Hal survived an arrow wound deep into his cheek, down into his skull and 30 days having it removed. No wonder he didn't flinch at atrocities in France and was a good leader of men. He kept order in his sick, rebellious army to win at Agincourt. It's a great pity he returned to the field after his marriage to Katharine de Valois, leaving such a young son on the throne, but that's Henry V.

Yes, this was the punishment for treason, not very nice, a terrible death. If you were noble and lucky, it might be reduced to beheading. Interesting story never heard before, thank you. He was a brave man.