The Face of a Tudor King

Westminster Abbey's quest to learn more about Henry VII's funeral effigy

Anyone who has visited Westminster Abbey will have been overawed by the sheer scale and magnificence of the imagery-laden Lady Chapel with its remarkable pendant fan vault ceiling, construction of which is owed to the ambition and vulnerability of Henry VII.

Conscious of the dubious nature of his claim to the throne, the first Tudor king sought to project the prestige of his fledgling dynasty through various means not least architecture. To this end, in 1502, the old Lady Chapel was pulled down and a new spectacle rose, a grand wonder that Henry intended to become his family’s mausoleum. For reasons any visitor becomes immediately aware upon entering chapel, it was justly regarded upon completion by John Leland as ‘the wonder of the world’ (I have previously written about this here)

Just consider the people buried within the chapel – Katherine of Valois, Margaret Beaufort, Edward VI, Mary I, Elizabeth I, Mary Queen of Scots, James I, Charles II, George II, William III, and many, many others of royal bearing. In the heart of the chapel rests the stunning bronze and marble tomb of Henry and his wife Elizabeth of York, encircled by an iron gate which created a private, chapel-like enclosure.

This ornate masterpiece was crafted in the Italian manner by a hot-headed Florentine artist by the name of Pietro Torrigiano, banished from his homeland for a string of violent incidents which culminated in breaking the nose of his colleague, Michelangelo. Torrigiano, described as having a thunderous voice, a formidable frown, and carrying himself more akin to a soldier than a sculptor, arrived in England either towards the end of Henry VII’s reign or early in Henry VIII’s. He soon impressed his new hosts with a series of realistic terracotta busts.

Having proven his talent, around 1512, Torrigiano was commissioned by Henry VIII to create the tomb of his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and was able to capture their likenesses with remarkable detail, depicting husband and wife lying side-by-side with their hands clasped in eternal prayer. In each corner were positioned four gilt bronze angels, with those on the east end holding aloft the royal arms with a pair of cherubs supporting the arms of the queen below. Though prone to arrogance and rage, deficiencies in character that would result in his days ending in a Spanish prison, Torrigiano was truly a master at his craft.

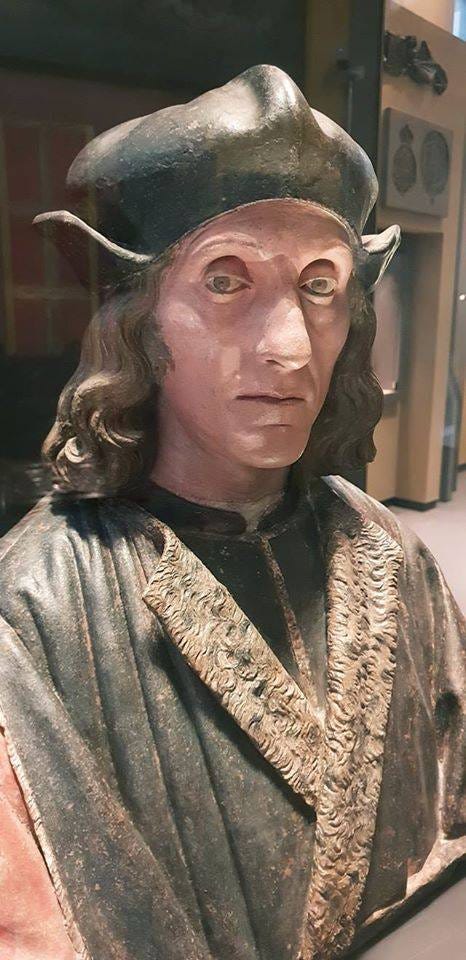

Once the modern visitor has finished gazing in wonder upon the array of Tudor tombs or the genius of Torrigiano, many pay an extra visit up to The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries, situated high above the abbey floor and which houses some of the finest treasures and artefacts the church holds in their possession. One such article is the funeral effigy of Henry VII, in which you can stare directly into the face of the mighty Tudor monarch himself. There is an air of quiet dignity about this figure, a sense of defiance as the centuries fall away.

Now, using the latest technological advances, the folk at Westminster Abbey are embarking on a fresh quest to find out more about this exceptional object, including whether or not it can also be attributed to the hand of the tempestuous Torrigiano.

But first, what is a funeral effigy and what purpose did they serve? Quite simply, during the medieval period, after the king or queen died, an effigy, or lifelike sculpture, of the monarch was usually carved from hollowed wood, with the face sometimes shaped from a wax or plaster cast taken from the subject shortly after death. The effigy, which had basic articulated limbs, was then dressed in royal regalia, including a crown and ceremonial robes. Sometimes wigs were then affixed to the effigy to render them more realistic, as the intention was to simulate the living person in every manner. Much better than displaying the decaying corpses of the monarchs, of course.

These life-size dummies would then be placed atop the coffin, visible to all during the funeral procession, with the people expected to pay the sculpture due reverence as though they were the living monarch themselves. Since the wood bodies were hollow, these would be stuffed with hay, which made them so light they could be borne easily by those carrying the coffin. Across the centuries, Westminster Abbey came into possession of a collection royal effigies after the subject was interred in their church, including Edward III, Anne of Bohemia, Katherine of Valois, Elizabeth of York, Mary I, Elizabeth I, James I, Charles II, and Queen Anne.

According to the account of Henry VII’s funeral, as recorded by the herald Thomas Wriothesley, after the king died at Richmond Palace on 21 April 1509, his body was washed then embalmed, before laying in state. One would have to assume it was at this moment a plaster cast was made of the king’s face. A fortnight later, he was placed in a coffin, and the funeral cortege headed from Richmond to London Bridge, across the Thames and into St Paul’s for the funeral service. After this was completed, the coffin began its final journey to Westminster Abbey where it was carried into the church by twelve members of the king’s guard and placed before the altar atop a small hearse, or structure.

Throughout the funeral procession, the king’s coffin was pulled along in a carriage drawn by seven sturdy coursers, each draped in black velvet bearing the royal arms. As was customary, atop the coffin was ‘an image or representation of the late king laid on cushions of gold apparelled in his rich robes of estate with the crown on his head, ball and sceptre in his hands’. This is almost certainly a reference to the effigy which now stands on display in Westminster Abbey’s galleries. The ‘image’ was created using his death mask.

On the morning of 11 May 1509, the foremost nobles and clergy of the realm gathered in the abbey’s Lady Chapel to hear three masses sung, before watching as Henry’s coffin was lowered into the vault that already contained the coffin of his queen, Elizabeth of York. The archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, dropped in a handful of soil before the king’s household officers snapped their staves of office and cast them into the grave, heralding the end of their service. The vault was closed. The only sound in the silent chapel came from the heralds, who after removing their tabards cried out in one loud voice ‘the noble king Henry the Seventh is dead’.

The funeral effigy itself had already been removed from atop the coffin before the interment took place, and soon disappeared into the bowels of the abbey, just another relic among many. In fact, the abbey’s collection of royal effigies weren’t treated with the utmost of respect in following centuries, and in 1872 were even pictured in the Illustrated London News stacked up one upon another without a second’s consideration for the treasure they were.

In 1907, the noted English antiquary William Henry St John Hope delivered a talk in which he updated his audience about the state of the royal effigies. He explained that the Henry VII effigy had lost its nose, though retained a fine body and legs. His investigations confirmed that the body was constructed chiefly from wood, which was surrounded with hay padding and then covered in canvas. The left hand was built upon a wire foundation formed to hold an orb, though the right was missing. The hay packing was prevented from slipping by huge wooden nails driven into the back and the front of the body.

It was St John Hope’s verdict that though the effigy’s clothing had been lost, it was nevertheless in good condition. He reported the reported the full effigy to be ‘a well-modelled complete figure of a man’, which stood 6ft 1inch tall. If an accurate likeness of Henry VII, this would tally with Polydore Vergil’s contemporary description of his Tudor master as a man whose height was ‘above the average’.

In 1941, however, during the height of World War II, a bombing raid caused considerable damage to the part of the abbey that housed the effigies. Though Henry VII’s effigy avoided complete disintegration from the initial fires, the water that poured into the chamber caused the sculpture to disintegrate over time, leaving it languishing in a ‘unsavoury, irreclaimable heap’ according to Robert Pickersgill Howgrave-Graham, assistant keeper of the Westminster Abbey Muniments. Henry’s effigy could not be salvaged for eight years, during which it sustained considerable injury.

Howgrave-Graham, however, was eventually able to access the effigies in the autumn of 1949, and though he judged their condition to be ‘utterly hopeless’, he embarked on a programme of conservation and restoration. In a talk he delivered in May 1953, Howgrave-Graham explained how, when he reached the effigies, he noted that 'glued joints had separated, limbs were detached, plaster was falling off almost daily and the hay of which two bodies were partly made was wet and rotten, and contained wood-lice and maggots'. Nevertheless, he was able to remove the effigies to a dry place where through a renovation programme he was able to arrest some of the decline.

Part of Howgrave-Graham’s restoration of the gravely damaged effigies was to reconstruct a nose for Henry VII. As he admitted, however, his attempt was simply ‘satisfactory’, and probably not in keeping with the nose the first Tudor king bore in life. He also noted that there were remnants of hair from where the wig had once been, that were proven to be human. They were red and grey in colour, and Howgrave-Graham speculated they may even have been the hair of the king himself.

Interestingly, and I’m not sure what to make of these statements, Howgrave-Graham said that he encountered at least four people who remarked that Henry VII had a ‘Welsh’ face. What a ‘Welsh face’ is, however, and how it differs from an English or a Scottish face for example, I am not entirely sure. There certainly are historical stereotypes of the Welsh being a small and dark complexioned people with black hair, but Henry VII, who nevertheless boasted English, French and Bavarian ancestry as well as Welsh, doesn’t exactly fit that mould even if it were accurate. Indeed, Howgrave-Graham went further and said that a person approached his effigy, ignorant of the subject, and said ‘who is your Welsh miner?’.

Nonetheless, the effigy that we stare at today, rescued from the rubble of war, is undoubtedly that of the first Tudor monarch, the Welshman responsible for the demise of Richard III, and the victor of the Wars of the Roses. Though he had probably grown gaunt from years of disease and ultimately the illness that took his life, descriptions of Henry from life state he was tall and slender. In fact, the funeral effigy looks remarkably similar to the only known painting that exists from Henry’s lifetime, namely the 1505 oil portrait that still hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

There is no question about the effigy’s similarity to the wonderfully vivid and realistic terracotta bust of Henry that can be viewed in the V&M Museum, one of Torrigiano’s English masterpieces. To any observer, they depict, unquestionably, the same person and strongly suggests both were crafted from the same death mask, as too was Torrigiano’s bronze bust of the king on his tomb.

And so, was Torrigiano responsible for the funeral effigy, as St John Hope hints at in his 1907 study when he attributes it to an Italian craftsman? This, and learning more about the sculpture’s construction, is what Westminster Abbey are now hoping to uncover in their latest investigations, conducted using the latest scientific advancements. As announced in their press release this week, the abbey’s curator Dr Susan Jenkins has sought the assistance of ThinkSee3D to rescan the head using the latest high-tech 3D technology.

ThinkSee3D are an Oxford-based studio that provide 3D content for museums, galleries and universities, including the British Museum, the V&A and the National History Museum. They are capable of 3D scanning historical artefacts, to physically reproduce high-quality replicas for exhibition, and create digital animation from thousands of images that can then be used as a high-resolution research tool. This form of digital content creation based on historical items can only enable to researcher to understand more about the past.

The findings will be revealed towards the back-end of 2025.

I likewise thought Henry VIi was not very tall.

Thanks Nathan for your generous posts. I am retired and don't pay to subscribe to anyone, it is a great pleasure to be able to read to the end of an interesting article without being stopped and told that only paying subscribers can read the whole article.

So he did look a bit like Mat Baynton:))) I always liked the scepticism in his eyes. Or was it evaluation and calculation?..