Secret Maps

The launch of an exciting new exhibition at the British Library

Welcome to another edition of ‘A Chronicle of Dragons & Cats’, and thank you for reading! If you have already subscribed, thank you for coming along on this journey. If you haven’t subscribed yet and like what you see, then click subscribe below. You’ll get the next post directly to your email and it’s FREE!

I had the great privilege of being invited to a private viewing of the British Library’s fascinating new exhibition ‘Secret Maps’, which showcases some hidden cartographic histories from across the last six hundred years that changed the world around us.

Maybe the kind folk at the Library knew that as a child it wasn’t necessarily history that I was obsessed with but rather maps. You rarely found me without an atlas in my hands when I was but a pup. And I know my neighbour Mal, who doubled up as my football coach, is known to remark that when he would drive a group of excitable (read naughty) kids to a game in one of the neighbouring valleys, I’d often be deeply engrained in one of his Readers Digest volumes, pulling out obscure geographical trivia and sometimes directing the way, even though he full well knew where he was going. I love maps and have never lost that interest. Give me an OS map and let me be. Here I am as a child, probably drawing a map.

So I was intrigued when I received the invitation, the follow up to their hugely successful ‘Medieval Women’ exhibition from last year, which you can read my review here. And also thrilled to run into friend and fellow historian extraordinaire, Elizabeth Norton, who has recently published the successful and riveting ‘Women Who Ruled the World: 5000 Years of Female Monarchy’. It seems like we both coordinated on wearing Tudor green but I assure you it was a coincidence.

So what is this new exhibition all about? Well, as curator of Antiquarian mapping Tom Harper explained, the British Library is in possession of some 4 million maps, documents which cover every part of the known world, and some of them from an age before what is now known wasn’t known then (looking at you Australia).

And these weren’t often created just for informative purposes - they didn’t just show the world, but helped shape it. Sometimes they even concealed as much as they revealed, which seems odd concept to those of us who have grown up with Google Maps on our own phones and concerns about creeping invasions of privacy. One thing that was particularly troubling to see was how Soweto, a sizable Black township on the edge of Johannesburg, was completely deleted from Apartheid-era maps, whilst enlightening was a 1937 map depicting public toilets in London frequented by gay men.

Many of these maps were never intended to be beheld by the everyday person like you or I (presuming you’re not someone with a high level of diplomatic or security clearance, a James or Jane Bond-esque figure who is following me for some light reading after a hard day saving the world. Anyway, I digress). These maps were, simply, designed for an agenda, and often one that sought to give a strategic or deceptive advantage to those ordering its creation.

Fortunately for those of us with an interest in shady practices of those who came before, lots of these maps have been declassified over the years and now the Library has chosen to publicly display 120 such documents from their bottomless archives. The selected maps are utterly engrossing, in the information they show, the details they sometimes purposefully omit, the context in which they were produced, like colonisation or war, and sometimes for how beautifully they are presented whether intentional or otherwise.

And of course, as with any modern exhibition space, there are plenty of fun interactive elements included, like spy holes and even the chance to find Wally. Yes, that Wally. What is interesting is the scaled down minimalist look of the space, which conveys the ‘behind closed doors’ ethos of the exhibition.

So, what treasures are held within, awaiting your gaze? Naturally, I cannot catalogue all of them here and of course I am drawn to those from the Tudor period rather than the Cold War, but these are some of the things that caught my eye.

Ther was Le Maire Strait from 1621, for example, a gorgeous globe created by William Bleau showing a crucial passing to the Pacific through the southern tip of South America, only charted for the first time by Europeans five years earlier. The Dutch East India Company actually tried to suppress knowledge of this passage to protect their monopoly and sought to silence Bleau and prevent him hawking his wares.

During the Second World War, escape maps were printed on lightweight silk for added durability. They could also be easily compressed for private storage, were quieter to carry than paper, and could get wet without damaging the print. But after the war, silk was in deep shortage, and so some maps were recycled for other uses. In this instance, some lingerie was made for Lady Mountbatten from an escape map of Italy presented to her by her-then boyfriend, and future husband, John Knatchbull. Pay attention and you will see the cities of Trieste and Milan on the Bra. A remarkable and eye catching piece that will be the centre of much attention during the exhibition’s run.

This 1542 map, known as A Chart of Europe, meanwhile, was produced by a French secret agent named John Rotz, who defected to Henry VIII that year. Rotz designed this map to provide Henry with invaluable maritime intelligence of the French fleet. It is an astounding decorative work with a shimmering golden border, and is both a work of art as well as a crucial strategic document designed to give England a military advantage in the very serious theatre of naval war.

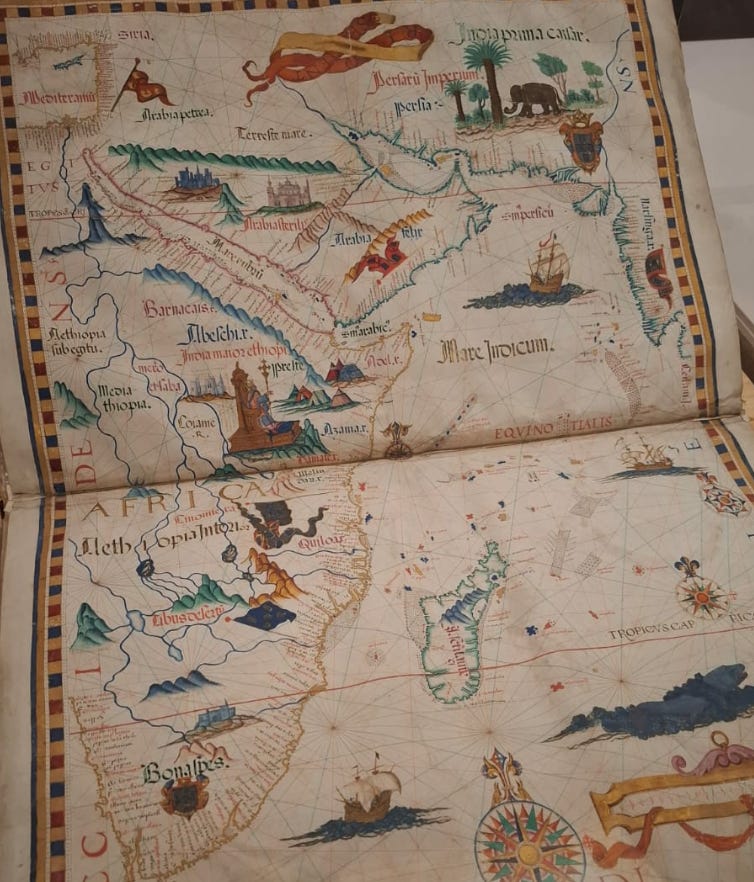

In 1558, meanwhile, shortly before her death, Queen Mary I commissioned this atlas of Africa for her husband Phillip II, King of Spain. It fairly accurately depicts the coastal regions, which by then were known to European explorers but the interior is speculatory. This maps and diagrams were designed to chart local rulers, people whom Mary and Phillip could create alliances or probe for opportunity for trade and influence. In many ways, it heralded the much-lamented scramble for Africa that would later come to fruition for European powers.

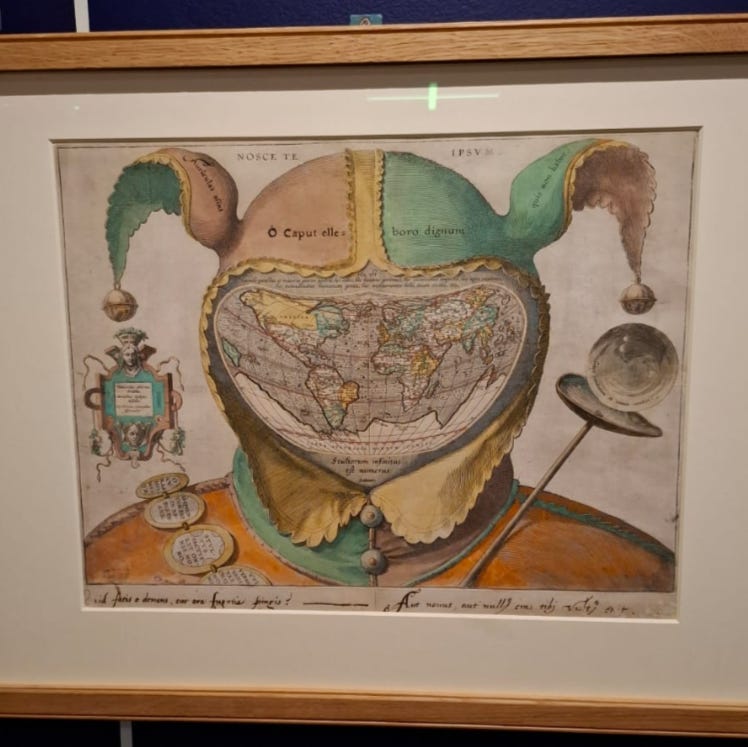

One of the more renowned pieces is a Flemish print from 1590 known as the Fool’s Cap World Map, in which a jester’s face is replaced by a map of then-known world. It is an enigmatic piece, and the motivation, agenda and creator are, as yet, unknown. Created at the height of the discovery craze, the map seems to be making a point about the foolishness of explorers who believe they have complete knowledge of the world around them – there is even a quote on the sceptre that reads the Ecclesiastes passage ‘Vanity of vanities, all is vanity,’.

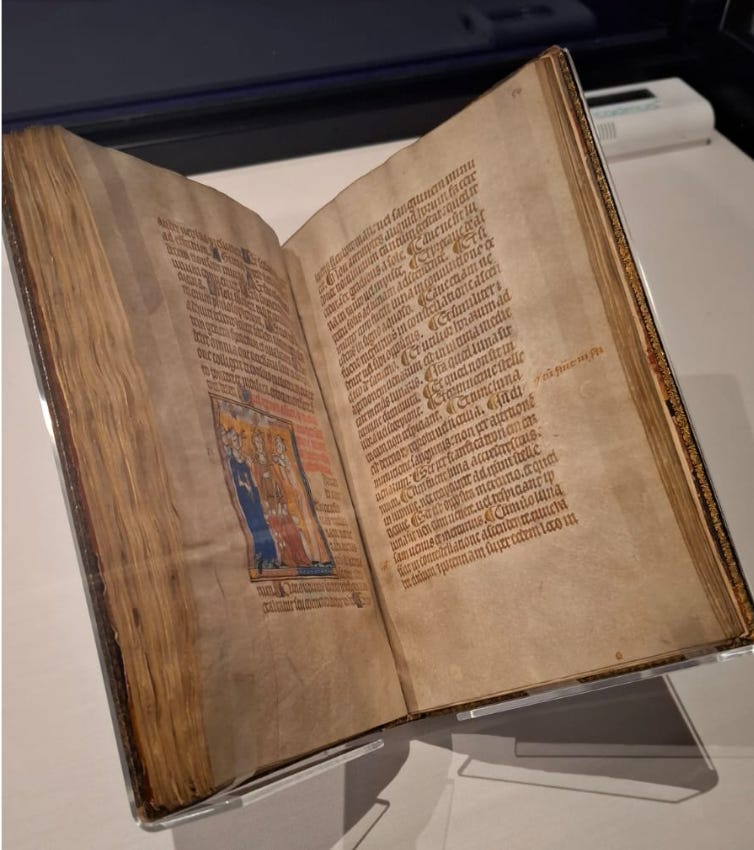

Other treasures of the past included a copy of the Secretum Secretorum, or The Secret Book of Secrets, created around 1326 for the new king Edward III and featuring a set of instructions allegedly given by Aristotle to Alexander the Great. The ‘secrets’ contained within include information on medicine, alchemy, ethics and astrology, a foundational knowledge it was believed kings could wield to great success for their realms. In many ways, as one of the most studied texts of the middle ages, its contents were not, in any way, considered secret as we would understand the term.

Finally, the Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis, or ‘Book of Secrets for Faithful Crusaders on the Recovery and Retention of the Holy Land’, was produced in 1325 by the Venetian Marino Sanudo to try and convince Pope John XXII to sanction another Holy Crusade. This book included secular charts, then a novelty, including maps of Palestine, the Mediterranean as well as detailed military plans of Jerusalem, Antioch and Acre for the campaign. The intention, of course, was not just religious but to expand Venetian political and trade influence further afield.

There really is something for everyone at this exhibition, such is the wide scope of its items, prudently curated to convey many eras, cultures, and subjects. Maps may just be paper, but they shaped the world in which we and our ancestors lived, empowering and disempowering in equal measure. This utterly absorbing exhibition shows how, whilst issuing a careful warning about our present inclination to trade our privacy to big tech in return for convenience. Perhaps there are lessons to be heeded from the past.

Secret Maps is running the British Library, London until 18 January 2026. Tickets are available on the British Library website.

That was really interesting, but OMG re the deletion of Soweto??! The exhibition is not for me: I can't find my way out of a paper bag, and consider maps instruments of torture, but my husband is booking a ticket as I write, so thanks for that Nathan!

Sounds like a fascinating exhibition! Have you ever seen the Mappa Mundi on display at Hereford Cathedral?