Margery Brews and the earliest Valentine's Day letter

‘My heart me bids evermore to love you truly over all earthly things’.

Every year on 14 February, romantic partners around the world exchange tokens of their love, perhaps flowers, a little gift, at the very least a card. Never forget the card - the funnier the better I find does the trick! But did you know that the earliest ‘Valentine’s Day’ message we presently know about belongs to the fifteenth century?

The Paston Letters are a wonderful resource, a real treasure trove for the fifteenth century historian in understanding the lives of men and women below the rungs of royalty. These are a collection of personal correspondence between members of one Norfolk gentry family and their wider network of associates. These were composed between 1422 and 1509 and are a remarkable survival that inform us of much that occurred, whether on a local, regional or national scale, during this troubled period.

As primary sources go, our knowledge of governance in the fifteenth century, relations between competing families, how events both major and minor were marked, the implementation and struggles with the law, the implications and consequences of dynastic warfare on the gentry, and the driving factors that led to rebellion and change in monarch would be altogether poorer without their survival.

The letters, which also include state documents, were largely retained by the Paston family until the death of William Paston, 2nd Earl of Yarmouth, in 1732, and three years later were acquired by the antiquarian Francis Blomefield. They subsequently passed through various hands until they were finally partially published by John Fenn in 1787. Since then, there have been various published editions produced, most notably James Gairdner’s collection between 1872 and 1904, with further letters uncovered.

Work continues to the present day in bringing the Pastons back to life through their own words. I think of

’s excellent Blood and Roses: One Family's Struggle and Triumph During the Tumultuous Wars of the Roses (2004) or Diane Watt’s insightful God's Own Gentlewoman: the Life of Margaret Paston (2024) among others.Most of the letters are now held in the British Library, with some in possession of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and Pembroke College, Cambridge. No history of the fifteenth century can be complete without referring to the Paston Letters, which provide context, gossip, intel, and insight to events that occurred six hundred years ago, all couched in a deep humanity that leaps off the parchment.

So, who were the Pastons? Well, the letters begin in earnest with William Paston, the only son of the Norfolk yeoman Clement Paston and his wife Beatrice Somerton. Through the patronage of his maternal uncle, this William became a lawyer and transformed the family's standing, expanding their property portfolio and rising to become Justice of the Common Pleas before his death in 1444. Within a generation, the Pastons had outgrown their old world, and were moving in high social circles, rubbing shoulders with aristocracy and even royalty.

With his wife Agnes, William had two sons, John and William - the latter was married to Lady Anne Beaufort, a daughter of Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, who before his assassination in 1455 was the kingdom's most powerful magnate, a noble of royal descent who had been the authority behind the throne for several years.

John Paston (often regarded as John I to differentiate him from his sons, John II and John III), was a Cambridge-educated lawyer who became a justice of the peace and a member of parliament. As the family head from the late 1440s to his death in 1466, he was drawn into a series of regional conflicts that adversely impacted his fortunes, of which he wrote about in great detail. His stormy relationship with his son John II, and his wife's attempts to calm relations are a recurring feature.

John II succeeded his father in 1466 and would spend much of his time asserting his claim to Caister Castle, which he claimed to be the rightful inheritor of. This brought John into conflict with some significant people, including the dukes of Norfolk and Suffolk, as well as Earl Rivers, the queen's brother. He would die with the matter unresolved.

Leaving no legitimate heir, his successor was his brother, John III, Both brothers had fought at the Battle of Barnet in 1471, and the latter succeeded to the family estates in 1479. This John would rise to serve as deputy to the Lord High Admiral of England, the earl of Oxford, and would fight on the side of Henry VII at the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487, for which he was made a knight banneret.

This is a very brief overview, and the family accomplished a wealth more, particularly in their native Norfolk. I implore you to check out the aforementioned work by Castor and Watt for more detail, or the Paston Footprints Project

The Valentines

But it allows me to bring you to the heart of today’s article, in more ways than one. In February 1477, John III received a letter from a young lady of his acquaintance known as Margery Brews. The two hoped to marry, but were prevented from doing so until their respective families could reach a financial settlement. Margery’s father, Sir Thomas Brews of Topcroft, was struggling with the dowry expected by the Pastons, noting he could not stow so much upon one daughter when he had other daughters to marry, whilst John III’s elder brother, confusingly also called John (II), believed he should have been consulted earlier in the discussions and been asked for permission for the match to proceed. He was, after all, head of the family.

Negotiations then, had rumbled on for some time, with the families remaining in touch. Margery’s mother Elizabeth Brews sent a series of letter to the man who hoped to become her son-in-law - in one, after discussing her husband’s demands, she added that her daughter, nevertheless, was a 'greater treasure' than mere money, 'a witty gentlewoman' that was 'both good and virtuous'. Even if she was offered a thousand pounds, Dame Elizabeth suggested she would be hesitant to hand her over.

Even so, in another letter John II sent to John III, his ‘most good and kind brother’, he noted that upon a visit to the Brews household, he found Margery’s father to be ‘so hard’ to deal with, though he did note he enjoyed the ‘goodwill’ of Margery and her mother Dame Elizabeth.

Such hesitancy from one or more of the parties involved in the arranging of a medieval marriage may have been commonplace, part of the negotiation process to secure the most advantageous deal possible, but thanks to the Paston Letters, we catch an emotional glimpse into the real-life human consequences that otherwise would have been lost to history.

Back to the February 1477 letter from Margery to John III. It seems that Margery was wholly devoted to the idea of marrying John, and was growing dismayed by the negotiations. Indeed, her mother Dame Elizabeth said she was such an advocate for John III, that she would not give her mother any rest until the matter was concluded.

In her letter to John, as written by the family scribe, Margery complained that she could not be of good health of body nor heart until she had heard from her love. She lamented how ‘My heart me bids evermore to love you truly over all earthly things’.

She explained that her mother continued to press their cause to her father, but was growing concerned that John would grow exasperated and turn away from her - ‘if you love me, as I trust verily that you do, you will not leave me therefore; for that if you had not half the livelihood that you have, for to do the greatest labour that any woman alive might, I would not forsake you’.

Quite simply, she loved John ‘truly over all earthly things’. This poor woman was the very definition of love-sick, yearning to be with her chosen one, determined to marry him regardless of his financial status or the desires of their parents. There was good reason she opened her letter by regarding him as her ‘right well-beloved Valentine’, and signed it ‘be your Valentine, Margery Brews’

Margery soon followed this up with another letter addressed to her valentine, pleading for the matter to reach a conclusion. Her father, she stressed would not part with more money than which he had already stipulated, £100 and 50 marks. But if John II was willing to marry her nonetheless, she would be the ‘merriest maiden on ground’ and he would find in her a ‘true lover and bedwoman’.

John III’s brother John II, also became a keen supporter of the match as time went by, noting in a March letter to the would-be groom that it was clear Margery ‘loveth you well’. John II would write at the end of the month to the brothers’ mother Margaret Paston, noting his concern at the ‘great hurt’ that would befall John III if the marriage ‘take not effect’. Clearly, Margery Brews was not the only one lovesick. John II confirmed he was content for the marriage to proceed, considering Mistress Brews’ ‘person, her youth, and the stock she is coming from’, before adding ‘the love on both sides’. To help smooth the deal and improve his status, John III’s mother granted her son the manor of Sparham, that would be enjoyed by the couple should they marry.

Fortunately for everyone involved, the Pastons ultimately refused to walk and accepted the terms of the hard deal Thomas Brews had driven, and Margery and John were married later that year, bringing the Pastons and the Brews families finally into union. Together, they had at least two sons (Christopher and William) and a daughter (Elizabeth) together, and later letters have Margery referring to her husband lovingly as ‘mine own sweetheart’ and how she thought of him ‘both day and night when I would sleep’.

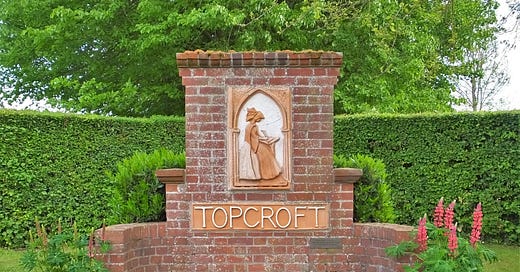

Margery died in 1495, probably around forty years old. The circumstances of her death are unknown, as is her final burial place. Her legacy, however, endures. In her ancestral home of Topcroft, Norfolk, a modern depiction of Margery can be seen when entering the village. She sits in solitude, quill in hand, writing to her well beloved Valentine.

Text of the Letter

Below is the full modernised text of Margery’s Valentine message:

"Unto my right well-beloved Valentine John Paston, squire, be this bill delivered.

Right reverent and worshipful and my right well-beloved valentine, I recommend me unto you full heartedly, desiring to hear of your welfare, which I beseech Almighty God long for to preserve unto his pleasure and your heart’s desire. And if it pleases you to hear of my welfare, I am not in good health of body nor of heart, nor shall I be till I hear from you. For there knows no creature what pain that I endure, and even on the pain of death I would reveal no more.

And my lady my mother hath laboured the matter to my father full diligently, but she can no more get than you already know of, for which God knoweth I am full sorry. But if you love me, as I trust verily that you do, you will not leave me therefore. For even if you had not half the livelihood that you have, for to do the greatest labour that any woman alive might, I would not forsake you. And if you command me to keep me true wherever I go, indeed I will do all my might you to love and never anyone else. And if my friends say that I do amiss, they shall not stop me from doing so.

My heart me bids evermore to love you truly over all earthly things. And if they be never so angry, I trust it shall be better in time coming. No more to you at this time, but the Holy Trinity have you in keeping. And I beseech you that this bill be not seen by any non-earthly creature save only yourself. And this letter was written at Topcroft with full heavy heart.

Be your own Margery Brews."

Learn more about the Pastons

For anyone who wants to take a deep dive of their own into the Paston Letters, you can access many of them through the below links, which take you to James Gairdner’s 1904 publication ‘The Paston Letters AD 1422–1509: New Complete Library Edition’

Subscribe for more - it’s free!

If you have enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing (completely free!) to receive future posts directly to your inbox. This will include historical snippets, book news and extracts, event details and also some insight into the world of the historical author.

If you’ve already subscribed, you are awesome and Vera says MIAOW with her paw raised in respect.

Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor

'Son of Prophecy: The Rise of Henry Tudor' is a 300-year history of one Welsh family, and how they emerged from the wilds of Gwynedd, navigated the murky and violent waters of Welsh-Anglo politics, and eventually found their way, almost improbably, onto the English throne. This story involves war, treason, escapes and love.

Fourteen years in the making, from defiant Welsh rebels to unlikely English kings, this is the story of the Tudors, but not how you know it. A BBC History Magazine 2024 Book of the Year, it is available to buy worldwide now HERE

The life so short, the craft so long to learn,

The assay so hard, so sharp the conquering,

The fearful joy that slips away in turn,

All this mean I by Love, that my feeling

Astonishes with its wondrous working

So fiercely that when I on love do think

I know not well whether I float or sink.

For although I know not Love indeed

Nor know how he pays his folk their hire,

Yet full oft it happens in books I read

Of his miracles and his cruel ire.

There I read he will be lord and sire;

I dare only say, his strokes being sore,

‘God save such a lord!’ I’ll say no more.

By habit, both for pleasure and for lore,

In books I often read, as I have told.

But why do I speak thus? A time before,

Not long ago, I happened to behold

A certain book written in letters old;

And thereupon, a certain thing to learn,

The long day did its pages swiftly turn.

For out of old fields, as men say,

Comes all this new corn from year to year;

And out of old books, in good faith,

Comes all this new science that men hear.

But now to the purpose of this matter –

To read on did grant me such delight,

That the day seemed brief till it was night.

…..

When I had come again unto the place

Of which I spoke, that was so sweet and green,

Forth I walked to bring myself solace.

Then was I aware, there sat a queen:

As in brightness the summer sun’s sheen

Outshines the star, right so beyond measure

Was she fairer too than any creature.

And in a clearing on a hill of flowers

Was set this noble goddess, Nature;

Of branches were her halls and her bowers

Wrought according to her art and measure;

Nor was there any fowl she does engender

That was not seen there in her presence,

To hear her judgement, and give audience.

For this was on Saint Valentine’s day,

When every fowl comes there his mate to take,

Of every species that men know, I say,

And then so huge a crowd did they make,

That earth and sea, and tree, and every lake

Was so full, that there was scarcely space

For me to stand, so full was all the place.

And as Alain, in his Complaint of Nature,

Describes her array and paints her face,

In such array might men there find her.

So this noble Empress, full of grace,

Bade every fowl to take its proper place

As they were wont to do from year to year,

On Saint Valentine’s day, standing there.

The poem above by Geoffrey Chaucer referred to the marriage of King Richard ii and Anne of Bohemia. It mentions the Parliament of Fowels. It is of course a fantasy piece. The origins of the feast of St Valentine go back to Rome and also to their own feast of love. Valentine was a Roman Christian martyr and his skull is buried in a Church nr the Temple of Faurnes.

I enjoyed this very much.