Henry and Elizabeth: The Marriage that made the Tudors

On 18 January 1486, Henry VII married Elizabeth of York. And so it all began...

“O, now let Richmond and Elizabeth,

The true succeeders of each royal house,

By God’s fair ordinance conjoin together,

And let their heirs, God, if Thy will be so,

Enrich the time to come with smooth-faced peace,

With smiling plenty and fair prosperous days”.

The famous words of William Shakespeare, describing the coming together of Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, and Elizabeth of York, at the end of his hugely controversial play, Richard III. Shakespeare, as we all know, was a playwright and not a historian, and one may take some issue with the concept that England would be blessed with ‘smooth-faced peace’ and ‘prosperous days’ by the coming together of these two distant cousins, particularly as he grew up under huge political and religious division at the back end of the sixteenth century. Nonetheless, he captures the basic truth which is that Henry and Elizabeth did indeed ‘conjoin together’ and formed one royal house out of two.

The much-heralded marriage took place, presumably in either Westminster Abbey or the nearby Palace, on 18 January 1486. In wedding Elizabeth, Henry honoured an oath he first made on Christmas Day 1483 in Brittany, itself pledged on the back of conspiratorial bargaining behind Richard III’s back between the groom and bride’s mothers, Lady Margaret Beaufort and Elizabeth Woodville.

Notably, when one considers Henry’s penchant throughout his reign to exploit any state occasion to project the majesty of his fledgling dynasty, there was little recorded about his wedding and it seems to have been conducted hastily. Henry’s blind court poet, Bernard André, is the sole source we have that gives some vague description.

In his biography of Henry, André notes that ‘Gifts flowed freely on all sides and were showered on everyone, while feasts, dances, and tournaments were celebrated with liberal generosity to make known and to magnify the joyful occasion and the bounty of gold, silver, rings and jewels’. He further remarked that ‘great gladness filled all the kingdom’, whilst the people ‘built fires for joy far and wide, and celebrated with dances, songs, and feasts in many parts of London’.

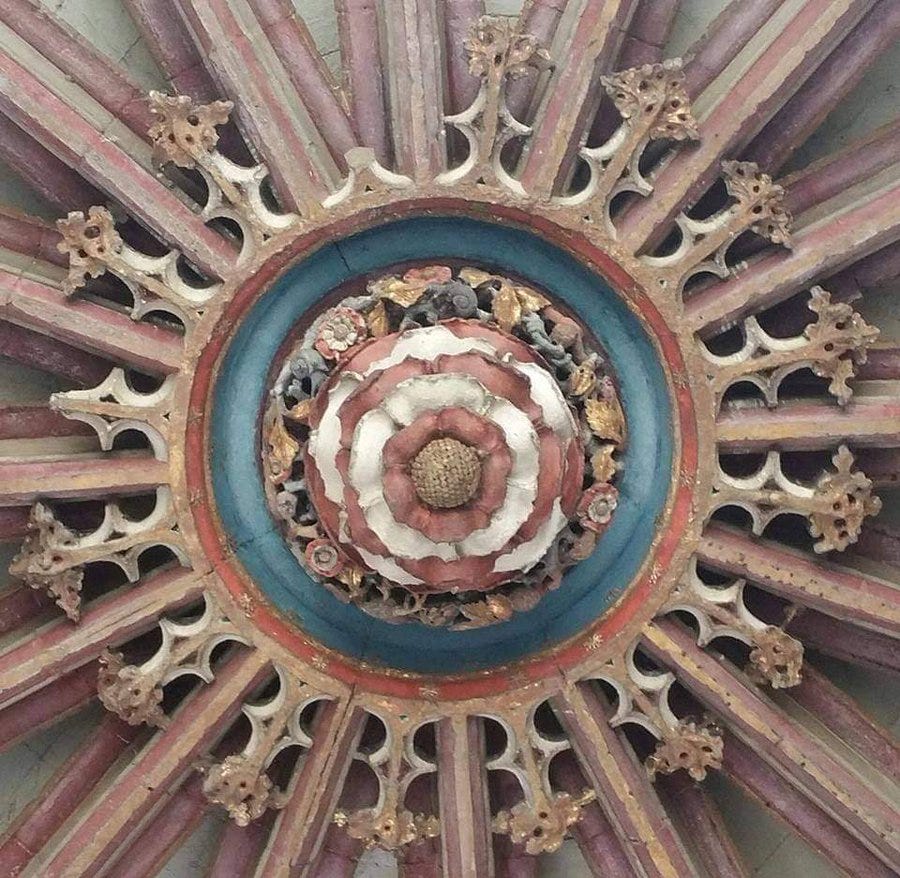

The date was also recorded in a Book of Hours owned personally by Margaret Beaufort, when next to 18 January, was written 'the day King Henry VII wedded Queen Elizabeth'. In York Minster, meanwhile, in 1515 a majestic Rose Window in York Minster was installed around 1515 to commemorate the marriage, featuring alternating panels of Lancastrian red and Tudor red and white roses.

Now, since Henry became king on 22 August 1485, that he didn’t marry Elizabeth for nearly five months has exposed him to criticism that he delayed the marriage and perhaps even sought a way out of his oath. This is unfair, and not predicated upon informed examination of the contextual facts.

In the months which followed Bosworth, the immediate focus of the new king, as novice as anyone to ever wear a crown, and his council was to attend to the pressing matter of governing a kingdom fractured by war, securing his position and conducting his first parliament.

Furthermore, there were two significant obstacles which needed to be settled before the wedding could go ahead; firstly, Elizabeth was legally a ‘bastard’ and secondly she was related to her potential husband in the fourth degree of kinship which required a papal dispensation to set aside. For a Lancaster-York union to succeed, it had to be considered valid in the eyes of the Church for any subsequent children to inherit the crown, and in this instance, the prospective bride and groom were within the prohibited degrees of kinship, sharing a common ancestor in John of Gaunt.

The first obstacle was swiftly handled by Henry’s parliament, which was in the process of reversing the act of illegitimacy that had been passed under Richard III. Elizabeth was once more regarded a legitimate princess of York.

Regarding the second matter, Henry and Elizabeth were also proactive. On 14 January 1486, in Westminster Palace, the would-be groom and bride both drew up a petition and presented it to the visiting Bishop of Imola, the Apostolic legate to England, seeking papal dispensation to marry. Their petition stated:

'on behalf of his most serene prince and lord, the lord Henry, by the grace of God king of England and France and lord of Ireland, of the one part, and of the most illustrious lady, the lady Elizabeth, eldest legitimate and natural daughter of the late Edward, sometime king of England and France and lord of Ireland of the other part, setting forth that whereas the said king Henry has by God's providence won his realm of England, and is in peaceful possession thereof, and has been asked by all the lords of his realm, both spiritual and temporal, and also by the general council of the said realm, called Parliament, to take the said lady Elizabeth to wife, he, wishing to accede to the just petitions of his subjects, desires to take the said lady to wife, but cannot do so without dispensation, inasmuch as they are related in the fourth and fourth degrees of kindred, wherefore petition is made on their behalf to the said legate to grant them dispensation by his apostolic authority to contract marriage and remain therein, notwithstanding the said impediment of kindred, and to decree the offspring to be born thereof legitimate'.

After two days examining the case, the bishop was satisfied with what he had been shown and assented to the union, having been granted power by the pope to sanction up to twelve marriages in England between couples related within four degrees of kinship. Just forty-eight hours later, Henry and Elizabeth were married. It is patently clear, that 'like a good prince according to his oath and promise' as sixteenth century antiquarian Edward Hall put it, Henry married Elizabeth as soon as was logistically possible.

Within weeks, Elizabeth of York was pregnant with an heir it was hoped would be the physical embodiment of the union between York and Lancaster, now represented by a Tudor child. The union was successful by any metric, and arguably one of the few medieval royal marriages with which we can be sure developed into a genuine match built on respect, affect, and even love. But that is another story for another time.

Lovely post on Elizabeth and Henry's wedding. If Elizabeth had been a Spanish or French Princess having to prepare and travel to England and negotiations taking place, the delay would have been longer than a few months. Nobody would be questioning any delay. The preparations alone must have taken some time to arrange.

Thank you for explaining what actually happened from the contemporary sources and the context of Henry and Elizabeth's union.

Legal complications, the coronation of Henry and Henry's settlement of a divided group of factions all had to be done first. All delays are perfectly obvious to me and practical. I think the criticism of Henry in this shows people don't read anything.

Worse still is the accusation put forward by PG in her popular novels that Henry raped Elizabeth or tried her out. There is absolutely no evidence for this and it makes no sense at all. Unfortunately too many people believe such nonsense. We don't even know if Elizabeth was pregnant before her wedding or if Arthur was simply a few weeks premature. If she was then we should allow that the couple fancied each other and good luck to them. Again there is no evidence other than the dates not quite working out for anyone to know either way. Arthur was healthy and 8 month babies are not uncommon.

Was it a love match? Probably not but it grew into a successful one, they were devoted as a couple, had 7 children and despite the politics, Elizabeth found life with Henry rewarding.

Excellent post - one question: Is there any possible truth to the rumor that Elizabeth of York was already pregnant at the time they got married? Could they have slept together in December, which might explain Arthur's early arrival? Just curious, although I'm guessing it's doubtful. Thank you for your wonderful insights and the sharing of your knowledge.