Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Hapus – Happy Saint David’s Day!

But who was Saint David, what is a Welsh costume, and why do we love leeks?

A very Happy Saint David’s Day to you all!

Yes, today is the 1st of March, which every year is a great day to be Welsh for it is the feast day of our patron saint, David (or as we know him in Welsh, Dewi, from the original Dewidd, itself taken from the Hebrew Dawid or Latin Davidus).

Everybody in Wales knows of Dewi Sant, and Saint David’s Day is one of the big occasions in the calendar for every Welsh school child. Children are sent to school wearing the Welsh national costume, or in some cases the venerated Welsh rugby jersey, with leeks and daffodils proudly pinned to their chests.

I remember with excitement how, each year, the photographer from the local newspaper would come in and take a snap, and the following week, there we were, in the news like celebrities. Sometimes, dawnsio gwerin would be performed by those sufficiently skilled in this form of folk dance. All of us would sing at least a few Welsh hymns during assembly.

In recent times, St David’s Day has become widely celebrated by adults as well, a day to be unashamedly Welsh, as if we needed another reason. There are now parades, concerts and pageants organised throughout the nation, with Welsh-themed talks, dinners and even dances put on. Even outside Wales, the day is marked, with the Empire State Building notably lighting up in red, white and green as well as the Tower 42 in London.

Welsh cakes and Bara Brith are consumed by the bucket load, bands like the Manic Street Preachers and Stereophonics are played on repeat, Welsh rugby jerseys and the iconic bucket hats are worn with great pride, and in my case, I’ll probably even wear my red Welsh daps (which is South Walian slang for trainers). Look at them, they’re lush, as we’d say.

In short, Saint David’s Day is an excuse for us to celebrate and champion Welsh culture, history, folklore, custom and the language. A Welsh day for the Welsh!

But wait, who even was Saint David?

Every schoolchild in Wales is taught about Saint David (Dewi Sant), and we recount some of his more famous miracles. As is often the case when dealing with historic figures, not least those who existed in sub-Roman Britain, the truth of David’s life as we know it today is hard to separate from the legend all Welsh people are familiar with today. Such is the curse of the historian, demolishing the stories we once loved with a probing, dubious eye.

There seems to be a consensus, however, that David did exist and was hugely influential amongst the Britons during the sixth century. Whether he performed miracles and was a holy man, of course, comes down to a matter of faith.

He merits a few mentions in early Irish sources, the countries now known as Ireland and Wales enjoying a fruitful cross-sea relationship during the early medieval period. One of these is the Catalogue of the Saints of Ireland, written around 730AD, where he noted as a holy man of renown alongside Gildas and Docus. A Breton account from 884AD meanwhile regards him as Dyvrwr’ – he was indeed later known in Welsh as Dewi Ddyvrwr, or Dewi the Waterman.

He was certainly mentioned in Armes Prydein (The Prophecy of Britain), a potent piece of poetic political propaganda dating from around 940 that called for all the Brythonic peoples to unite and face down the Saxon threat – it was hoped these people would stand beneath David’s banner to do so.

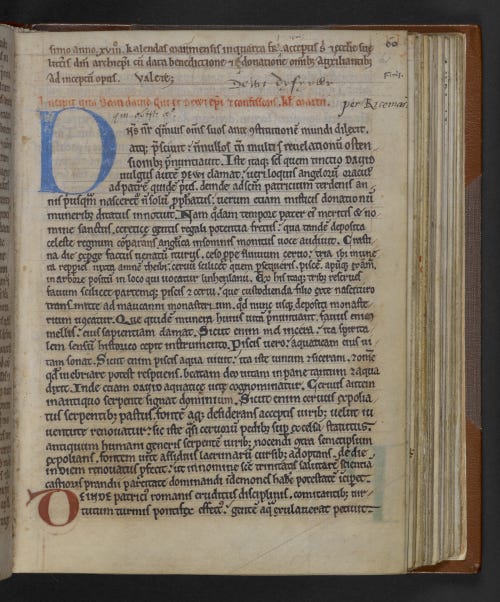

The most insightful source we have for David’s life, however, and the one which has shaped our modern knowledge of the saint, is found in the Latin-language Vita sancti Davidis episcopi (The Life of David, later translated into Middle Welsh as Buchedd Dewi and subsequently English). This was produced around 1095 by a Norman monk named Rhigyfarch, the son of the Bishop of St David’s, Sulien (now in the British Library as Cotton MS Vespasian A XIV)

Now, Rhigyfarch’s Life was constructed more than five hundred years after it’s subjects alleged death, and as to be expected, its veracity, not to mention its writer’s agenda, have been justifiably questioned. He claimed that is sources were scattered moth-eaten archival writings he had come across in the cathedral which by then already bore the saint’s name, access to which he presumably enjoyed on account of his father’s position.

Context is always important when looking at history, and it should be noted that Rhigyfarch composed his account at a moment the Welsh people were coming under heavy pressure from expansionist Norman forces, with much of what we now regard as Wales falling into Norman control through great violence. It stands to reason that Rhigyfarch sought to advance, even enhance, the prestige of the Welsh church at this crucial moment and to assert its independence from the diocese of Canterbury by raising the standing of one of its famous sons.

According to Rhigyfarch, first and foremost, David’s birth was foretold by angels to Saint Patrick thirty years before he was born. Patrick was upset that another was to supplant him, but was comforted when the angel revealed to him that his duty was to head to Ireland to carry the message.

Three decades later, a beautiful and graceful nun named Nonnita was seized by Sant, the son of the king of Ceredigion, who forced himself upon her. This gave her son a royal lineage, descended from one of the many petty kingdoms that emerged in the vacuum left after the Romans departed Britain. Throughout her subsequent pregnancy, Nonnita subsisted on bread and water only, and the place where her boy was conceived, a well was sprung and two stones for her to rest her head and feet.

During her pregnancy, Nonnita entered the local church where the renowned Gildas was preaching. In the unborn child’s presence, however, Gildas’s throat dried up and he could not preach before Nonnita, which was taken as a confirmation of her child’s greater holiness than Gildas’s. The child was given by God, Gildas said, ‘the privilege and monarchy and the leadership of all the saints of Britain forever’, and that ‘by the privilege of honour, the brilliance of wisdom, and the eloquence of speech’, the child would ‘surpass all the teachers of Britain’.

David was born during a great and terrible tempest, that involved flashes of lightning, the clash of thunder, and excessive downfall of hail and rain. From his earliest moments, miracles were associated with him, including healing a blind bishop during his own baptism. This seems to be a recurring theme, for David would also heal the blindness of his teacher Paulinus. On another occasion he happened across a grieving mother and her dead son. David tried to comfort her, but the mother fell at his feet and begged him to have mercy upon her. David, full of compassion for the woman’s pain and weeping at her pain, beseeched God to return life to the boy, which He did.

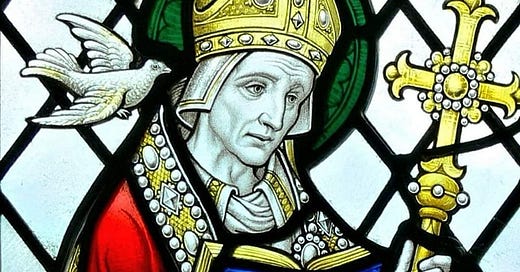

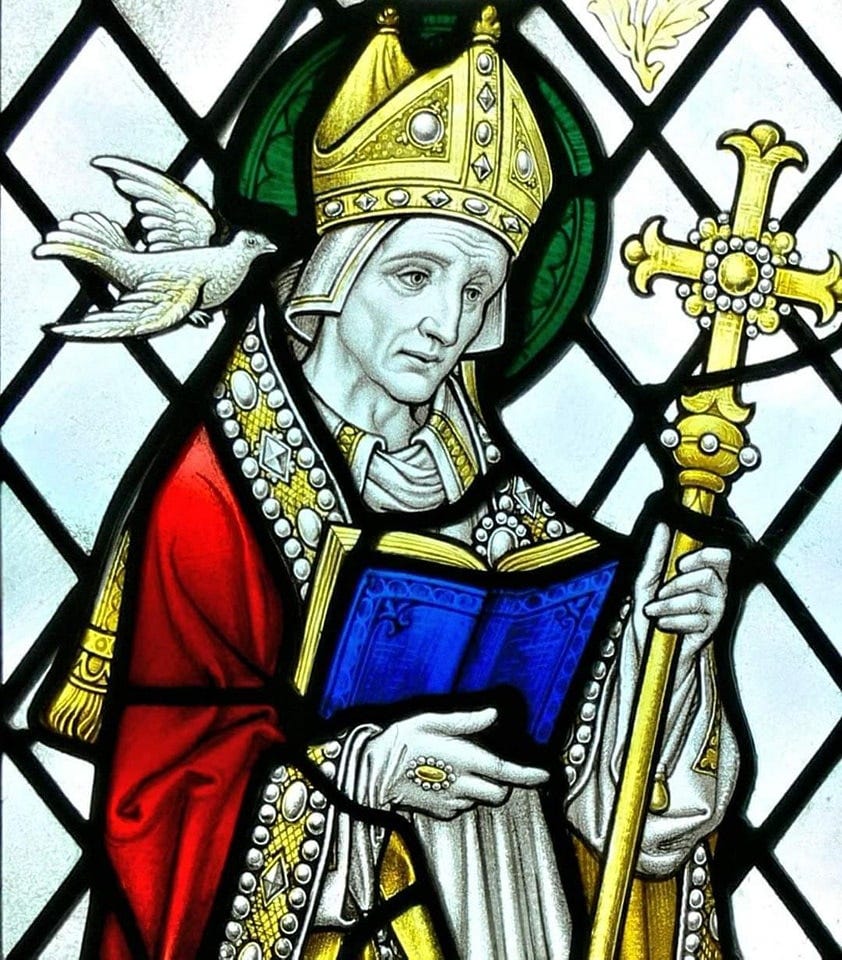

David’s most enduring miracle occurred at the Synod of Brefi, a meeting of all the bishops, abbots and priests in Wales to oppose the teachings of Pelagius, which were considered heretical. Still just a junior churchman at the time, when David attempted to speak few people could hear him. And so, beneath his feet, the ground began to rise, giving him a platform from which he could lead the throng. His voice was like a trumpet as he proclaimed the Gospel and upon his shoulders for the duration was a white dove sent from Heaven, which remains his symbol today. Thereafter, his authority established, David would be regarded in old age as the head of the British race, establishing the monastery that now proudly bears his name.

Throughout his life, David was noted for his ascetism, even in an age where leading an austere life was the norm. He only ate bread and drank water, maintaining a clean body and mind. At the command of an angel, he travelled to Jerusalem on pilgrimage, and has been credited by Rhigyfarch with founding twelve monasteries, including at Glastonbury and Bath. His work done, David died on 1 March, a Tuesday, the year of which has traditionally been given as 589AD.

Writing a century after Rhigyfarch’s hugely influential account, but no doubt drawing on his own local experience, the Welsh-Norman priest Giraldus Cambrensis, known as Gerald of Wales, noted approvingly that David was ‘extremely devout and lived a most saintly life’, a man who advocated for hard work and temperance.

The Cult of David

With the championing of men like Rhigyfarch and Gerald, the cult and fame of David grew throughout the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Indeed, in 1120, Pope Callixtus II was even persuaded to canonize David, going so far as to announce that two pilgrimages to his monastery was akin to one to Rome. By 1200, there were more than sixty churches in South Wales dedicated to David, and his principal monastery was even given due reverence by visiting English monarchs who recognised his holiness, including William the Conqueror, Henry II and Edward I.

Clearly established in South Wales, the cult even spread into England after the 1485 accession to the English throne of Henry Tudor, who had been born in Saint David’s Pembrokeshire backyard. With a Welsh born, blooded and bred king seated upon the English throne, and one willing to grant his countrymen opportunity to flourish, there was something of a Cymric exodus, with London in particular hosting a sizable Welsh community that has never quite gone away – yours truly is just the latest in a long list of Welsh people who have made the city their home.

In fact, such was the sudden emergence of a Welsh community that early in Henry’s reign, Edward ap Rhys was granted permission to open a beerhouse in Fleet Street that was called ‘The Welshman’, and the king himself even took to rewarding the Welsh in his employ with money so they could celebrate the feast of Saint David’s each March. Though Saint George and Saint Edward the Confessor were naturally the official saints of choice for English kings, Henry nevertheless had no issue with David being recognised by the Welsh.

When the Reformation was imposed on Wales as it was England by the government of Henry VIII, David’s cult collapsed, with his shrine destroyed and his relics scattered. This was not unique to David, of course, as Protestantism took hold of the kingdom. Knowledge of Saint David did not completely fall away, however, as shown by his inclusion as one of the Seven Champions of Christendom in 1596, alongside saints George, Andrew, Patrick, Denis, James Boanerges and Anthony the Lesser.

There is strong evidence that Welshmen and women in London continued to commemorate their national saint and their patriotism into the Stuart period by looking at the level of hostility they incurred for doing so. In the entry for 1 March 1667, the diarist and politician Samuel Pepys made the following observation on his daily duties:

“back again to the office, and in the streets, in Mark Lane, I do observe, it being St. David’s day, the picture of a man dressed like a Welchman, hanging by the neck upon one of the poles that stand out at the top of one of the merchants’ houses, in full proportion, and very handsomely done; which is one of the oddest sights I have seen a good while, for it was so like a man that one would have thought it was indeed a man”.

Grim. In a satirical print by William Holland in 1790, meanwhile, the Welsh were shown celebrating Saint David’s Day by toasting their cheese while wearing leeks in their hats, with some visible sheep heads in the background. Playing into all the stereotypes.

Fortunately, a solid revival in interest in Welsh history and culture began in the following century, which included the formation of influential Welsh-focused societies like the Honourable and Loyal Society of Antient Britons in 1715 and the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion in 1751, the Welsh Charity School in London in 1716, as well as various Eisteddfodau throughout Wales, which renewed David’s standing among his flock. The first English language book about David was written by Arthur W Wade-Evans in 1923, which again furthered David’s legend. Though we live in an increasingly non-religious Wales today, David’s standing remains high.

David’s Leek

As mentioned earlier, on Saint David’s Day, many children go to school in the Welsh national costume. This outfit owes its origins in its current guise to the middle of the nineteenth century when there was a conscious attempt to revive Welsh culture, arts and the language. During the 1830s and 1840s, the wife of a Gwent ironmaster named Augusta Hall took a great interest in the concept of a national dress, adapted from the practical wear of the rural Welshwomen. Popularised through painting, this soon caught on and by the end of the century, a Welsh costume that consisted of an apron, a shawl, a gown, a underskirt and a distinctive, high crowned, broad brimmed black hat was widely recognised.

By the time Sydney Curnow Vosper completed his vivid 1908 painting Salem, featuring an elderly Welshwoman in this costume, it had become iconic. Today, mass-produced recreations of this costume are worn with pride by schoolgirls every 1st of March (or based on my sister’s dismay every year, perhaps reluctantly!).

For boys, a similar Victorian-esque costume may be worn, but often, we would just wear a Wales rugby jersey and stick a leek to our chests using a safety pin. The leek is a national symbol of Wales, after all, not just a random root vegetable we grabbed at the greengrocers on the way into school.

But why a leek? Look – the truth, like many matters of a historical nature, is lost to us today. We are left with shadowy myths that over the centuries have merged seamlessly into fact.

The leek as a symbol indicating Welshness is difficult to date earlier than the 1530s, and even then, it is presented in an English context. Sure, in the fourteenth century, Welsh archers were noted to be wearing green and white, the colours later adopted by Henry Tudor as his own personal livery colours and which today form two of the three colours of the Welsh national flag, but as far as I’m aware, whether this is related to the leek or not is questionable.

In the Privy Purse Accounts of Princess Mary (the future Mary I) for 1536-1542, however, the daughter of Henry VIII is presented on at least two separate Saint David’s Day with a leek. Though she had never been invested with the title Prince(ss) of Wales, as Henry’s longtime legitimate heir, she was widely regarded by many as just that, particularly when she was sent to Ludlow to nominally head up the Council of Wales. But for the Princess to be given a leek suggests it was, at least by this date, regarded as Welsh-ish, whether that was accurate or otherwise.

By the age of Shakespeare, the leek was firmly associated with the Welsh and Saint David. In the Bard’s excellent 1599 play Henry V, in Act V, Scene 1, the amusing Welsh captain Fluellen remarks that the Welshmen did ‘good service in a garden where leeks did grow, wearing leeks in their Monmouth caps’, before mentioning that the King, born in Monmouth, wore a leek in his hat himself upon ‘Saint Davy’s day’.

One of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, a poet named Michael Drayton, wrote in 1613 how ‘the reverent British saint’ would sit in an aged cell, contemplating life and eating only leeks he had gathered from the fields. A catchy ballad dating from 1630, meanwhile, known as ‘The Praise of saint Davids day showing the Reason why the Welshmen honour the Leek on that day’, attempts to do just that, and in many ways, gives us the enduring story we accept today. In this otherwise pro-Welsh ballad, it is shown that during one unidentified military encounter the Welsh were struggling to maintain order and began to lose order in their ranks. In order to seek out and identify one another, as they crouched in the field of battle, they plucked leeks from the ground and placed them in their hats so they knew where lay their compatriots. Thereafter, the ballad said, ‘an honour on Saint Davids day, it is to weare a Leeke’.

Many have tried to build a wider story around this, and even pinpointing the particular engagement with the Saxons, Normans, or English, where a group of resourceful Welshmen in a spot of bother spontaneously came up with a foolproof plan to outwit their enemy. Of course, anyone who has seen a leek will know how impractical this would be, and it would be surprising if it has any authenticity.

Nonetheless, such accounts as these helped the leek become the recognised symbol of Wales it remains today, widely visible not just during Saint David’s Day, but during any other outpourings of Welsh national pride, not least on a rugby matchday when some brandish large inflatable leeks! Every 1st of March, the Welsh Guards, a regiment in the British Army whose cap badge is a leek, even place a leek in their caps, replicating Shakespeare’s Welshmen. The Royal Welsh go one step further and eat them! Between 1985 and 2008 the reverse of the British £1 coin bore a leek with a royal diadem to represent Wales. And of course, no self-respecting Cawl, a sumptuous and hearty Welsh stew, can be made without copious amounts of sliced leek!

Who knows why, but the leek is unquestionably a symbol of Welshness today and has been since at least Tudor times, despite not even being a vegetable native to Wales! Incidentally, another recent national symbol of Wales that is not native to the country, the daffodil, is known in Welsh as Cenhinen Bedr, or Peter’s leek.

Do the Little Things

Dewi Sant is an iconic figure in Wales today, the person who represents our nation, our patron saint. He is our guy. The city that bears his name, where it is traditionally believed he was born and established his monastery, is famed in its own right these days as Britain’s smallest city (except for the City of London, anyway). Anyone who has visited this charming place knows exactly how small this city is – it’s scarcely a village.

The present day Norman cathedral is beautiful, and unlike many other large churches, is not constructed upon a hill but rather in a dip in the valley, so you actually walk down to it rather than up. This is because the original monastery that once stood here suffered repeated raids from Vikings passing along the nearby coast, so when it was rebuilt, it was purposefully concealed. Much of the cathedral today is late 12th century, with some notably Tudor additions, not least the rebuilding of the fan vaulted Holy Trinity Chapel and the Irish oak ceiling in the nave. Right before the altar now stands the tomb of Edmund of Hadham, better known as Edmund Tudor, the father of Henry VII.

Back to David, the person responsible for there being a cathedral here in the first place. Part of his final sermon (at least, as recounted by Rhigyfarch) has entered Welsh vocabulary, a piece of wisdom still routinely said in Wales 1400 years later. Before his adoring following, David counselled them to ‘Be joyful, and keep your faith and your creed, and do the little things that you have seen me do and heard about’. In Welsh, ‘Do the little things in life’, or ‘Gwnewch y pethau bychain mewn byd’, can still be heard today.

And what a lovely message that for us all in this complicated and often overwhelming life we lead. Wise advise from a wise man.

Do the little things.

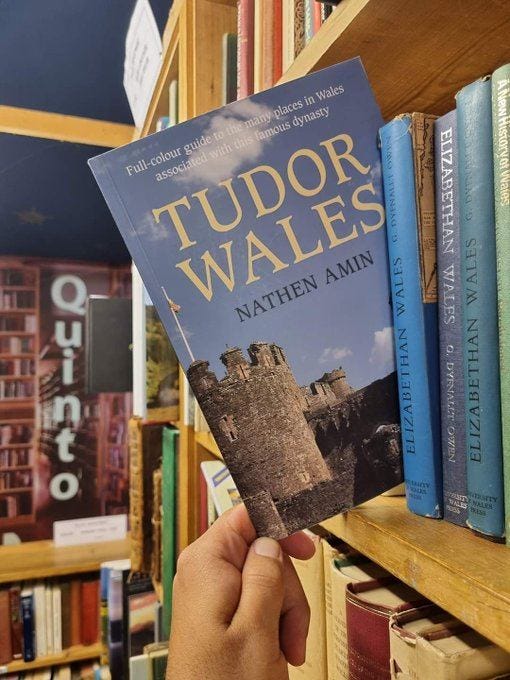

Tudor Wales: A Guide

In 2014, my first book ‘Tudor Wales’ was published, a guidebook in which I take a look at the copious places you can visit today in Wales that are either associated with the Tudor Dynasty or were noteworthy during the Tudor Period. Many churches, abbeys, castles and country houses were included, some famous and others lesser known.

If you’re planning a trip to Wales anytime soon (and if you aren’t, you should be, it is beautiful), consider picking up a copy and taking it with you, a handy guide on your travels!

![May be an image of text that says "MENS' M'CIJ [1537-8.] 61 [FOL. 41. b.] XVs. XV S. Childe lim geuef amonge the yeomefi of the kinge gard bringing a Leke to my lade grace ס saynt Dauid Daye tim geuen to thie Nurce and mydwite of my lorde Cobhan my lade grace being godmother to the same xxvi xxvis.ijd รี. iijd. lim σй to Phillip the luter xj..iijd. lữm geuen to george Brigwhis fünte bringing a kydde to my lade gče lim geuen to to a pore woman of Worcestĩ- shyre bringing Chickens xxd. d. xX iij.iijd." May be an image of text that says "MENS' M'CIJ [1537-8.] 61 [FOL. 41. b.] XVs. XV S. Childe lim geuef amonge the yeomefi of the kinge gard bringing a Leke to my lade grace ס saynt Dauid Daye tim geuen to thie Nurce and mydwite of my lorde Cobhan my lade grace being godmother to the same xxvi xxvis.ijd รี. iijd. lim σй to Phillip the luter xj..iijd. lữm geuen to george Brigwhis fünte bringing a kydde to my lade gče lim geuen to to a pore woman of Worcestĩ- shyre bringing Chickens xxd. d. xX iij.iijd."](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_du_!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5ece6441-24c2-4f89-8fce-f2d42f4c2aa7_434x362.jpeg)

Very interesting! There's Welsh Week here in NYC, appropriate as Llandaff-born merchant and Signer of the Declaration of Independence Francis Lewis lived here. I'm one of many Americans who has Welsh roots (Mathew, Herbert, Fleming, Bowen and Merrick), more common than one might imagine. And I shall be mindful of doing 'the little things'. (Adorable childhood photo, by the way.)

Very interesting and enjoyable read, thank you.