Have you ever wondered how the early Tudors marked Christmas? Well, I hope you have because that is exactly what this article will explore!

Now, Christmas traditions in the UK (and indeed, the rest of the world) may appear set in stone – for example, the tree (real or fake), the songs (religious or secular) and the food (good and bad) – but it’s been very much an evolving process since the earliest days people began marking the birth of Jesus Christ. Indeed, midwinter and the winter solstice as a period of celebration in this part of Europe predated Christianity, some pagan traditions of which were adapted across the centuries.

The way the Tudors celebrated Christmas, taken from the Old English word for ‘Christ’s Mass’, differed somewhat from the way we do today, even if we discount the technological advances – there were no Christmas trees in living rooms for example (though homes were decorated with evergreen plants like holly, bay and ivy), but the core concepts of family, community and feasting were still integral even if religious observance remained the central aspect.

Five hundred years ago, the Christmas festivities only began in earnest on Christmas Day itself, lasting for twelve days until 6th January (hence the twelve days of Christmas). The end date marked the Feast of Epiphany, which commemorated the visit of the Magi to the infant Jesus. Our forefathers and mothers certainly weren’t getting into the Christmas spirit months in advance like some of us today!

In fact, it was quite the contrary. Starting on the first Sunday after St Andrew’s Day, which was 27 November, Advent (from the Latin word adventus meaning ‘second coming’) was a period of atonement and penance, in which people prepared themselves spiritually and liturgical readings focused on the Virgin Mary. For many, as well as a period of intensive prayer and abstinence, this involved some degree of intermittent fasting, avoiding meat and dairy products in particular. The run-up to Christmas was certainly not then, a period of overindulging as the big day approached, consuming more with each passing day. Though framed as an act of religiosity, such discipline also, of course, allowed supplies to be rationed out across the bleak mid-winter.

During the 1530s, the industrious antiquarian John Leland was handed a royal commission by Henry VIII and travelled around England, visiting many monastic libraries to consult their manuscripts. His transcriptions and notes from this mission provide much valuable insight into the early Tudor period, not least how Henry VII and Elizabeth of York marked Christmas in 1487

That year had not been an easy one for the first Tudor king. His crown, even his life, had come under severe threat from hostile forces within and without his kingdom, although the resilient king ultimately succeeded in overcoming his enemies. The first six months of the year had seen Henry preoccupied with suppressing the conspiracy nominally led by the pretender Lambert Simnel, which he comprehensively defeated in battle at Stoke Field in June. Since he had won his own crown in battle, overcoming and killing Richard III, the Tudor king no doubt appreciated more than anyone how fine the margins were when stood on a medieval battlefield watching the chaos and frenzy unfold before you. By the end of the day, around 5,000 men lay dead, but his crown remained upon his head.

From the battle, Henry headed north into Yorkshire, where the chronicler Edward Hall wrote that he wanted to ‘weed out and purge his land of all seditious seed’, and then on to Newcastle. From the very north of his kingdom, he turned around and returned south, passing through Durham, Richmond, Ripon, Pontefract, Newark, Stamford, Huntingdon and St Albans, detouring along the way to Warwick to collect and be reunited with his queen, Elizabeth of York. When they had parted before the battle, they never knew if they would be reunited.

By the start of November, after one battle and several hundred miles of travelling, Henry was back in his capital, ready to open the second parliament of his reign. Whilst all his nobles and lords were in London, the king took advantage to arrange the belated coronation of his wife Elizabeth. Though one chronicler noted he ordered this ‘for the perfect love and sincere affection’ he bore her, he also wisely noted that if he wanted to ensure the future loyalty of the Yorkists, it would pay well to crown his Yorkist wife.

The queen was crowned on 25 November, which gave the royal court one final knees-up before the Advent period commenced. Rebellions, battles, parliaments and coronations, followed by a period of penance, once imagines Henry VII looked forward to the Christmastide that year for a period of much-needed relaxation.

The king and his court remained in Westminster until around 18 December when, as he had for the previous two Christmases, he departed by river for Greenwich Palace. Once known as the Palace of Placentia, or pleasure palace, this state-of-the-art royal residence was constructed forty years earlier and lay on the banks of the Thames, a scenic riverside retreat from the rush of the city. It would be here, surrounded by lush countryside and the tidal waterway, that Henry ‘kept his Christmas full honourably’, according to Leland’s manuscript.

On Christmas Eve, the document continues, ‘our said Sovereign Lord the king went to the Mass of the Vigil in a rich gown of purple velvet furred with sables’, the sable being a small brown mammal highly prized for its luxuriously soft and silky fur. Henry didn’t go alone, of course, being ‘nobly accompanied’ by many of his foremost nobles, repeating the process again for Evensong, this time having his Officers of Arms with him.

The divine service was performed by someone Leland refers to as Lord John Fox, but this is presumably an error, and he means Richard Foxe. This Foxe was notably close to the king, having first entered Henry’s service when the latter was in penniless exile in France, little more than a Welsh rebel. Foxe, then an English student in Paris, flocked to Henry’s side, for which he was attainted by Richard III. When Henry invaded England and remarkably became king against the odds by deposing Richard, Foxe benefitted greatly – by January 1487, he was already Lord Privy Seal and bishop of Exeter, the beginnings of a prestigious career. The churchman performing such a prestigious religious role on Christmas Eve then, was surely the king’s great friend.

The following day, Christmas Day, marked the celebration of God taking human form himself for the salvation of humanity, and as expected, required much from the laity in their observances. Three Masses in total would need be heard, but even so, around this the religious shackles were loosened somewhat and the people, whether peasant or prince, finally were able to feast and party with abandon. December was and is one of the most miserable months of the year – it’s cold outside and dark for large parts of the day, so staying indoors and making merry was certainly a sensible way to pass time for the next twelve days. Fortunately, even those at the lowest rungs of the social ladder were granted a rare period away from their daily toil in the fields, and everyone took full advantage of the break, often sharing the load by celebrating together.

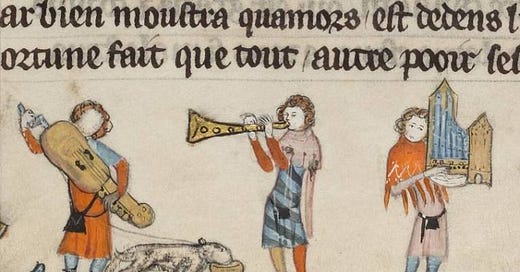

We have a glimpse into some of the celebrations expected at Christmastime from a letter written by Margaret Paston to her husband John on Christmas Eve in 1459 – some of the usual activities she mentions are masquerading (masked dances sometimes known as disguising), the playing of musical instruments like the harp and lute, singing and other loud pastimes, and the playing of games like backgammon, chess and cards.

After a lean month of abstinence, the smell and sounds around homes, from those in a modest village up to the royal court at Greenwich, must have been intoxicating in many ways. Of course, to help things get moving were actual intoxicants like hippocras, a warm spiced wine drink enjoyed by those of means. For those short on funds, there was always ale, sometimes even given away by the church.

In Leland’s document, it notes that on Christmas Day, Henry VII celebrated with a dinner in the ‘great chamber next to the Long Gallery’ whilst ‘the Queen and my Lady the Kings Mother’, his wife Elizabeth of York and mother Margaret Beaufort, ate their meals alongside their ladies-in-waiting in the Queen’s Chamber.

What food was consumed specifically is unmentioned, but as ever with the fifteenth century, the dishes available would have been varied and dictated by the season and weather. Typical winter fare for a royal household during the period would have included meats and fish like beef, pheasant, peacock, partridge, quails, venison, goose, duck, swan, capons, eels, pike, heron and rabbit, along with cheese, bread and a variety of sweetmeats and spiced cakes. Turkey was not available, not being an animal known to the European at this time. Looking at the menu for Elizabeth of York’s coronation feast just a few weeks earlier confirms these were all available in the winter of 1487.

One traditional dish widely available was frumenty, a pudding made from boiled wheat, cream, mace, nutmeg, barley, eggs and milk often flavoured with almonds, currents and the like. A huge Christmas Pie, meanwhile, consisting of thirteen ingredients, including suet, sugar, dried fruits and shredded meat, each representing Jesus and his apostles, was probably also enjoyed. Mince Pies were also consumed, though unlike today these were made from actual shredded meat mixed with spices and fruit.

The centrepiece of the medieval Christmas dinner table, however, was a roasted boar’s head garnished with rosemary and bay leaves, perhaps with an apple in its mouth. The boar, fierce and dangerous to the death, was one of the more difficult wild animals to kill on a hunt, and therefore highly prized. It was a dish worthy of a king.

Around feasting and religious observances, Henry likely spent much of this period playing games. The historical record reveals he thoroughly enjoyed gambling, although based on his losses, he doesn’t appear to have been a proficient in placing a wager. His payment accounts record him losing money regularly through cards, dice, chess and even tennis. Elizabeth of York’s own personal accounts also show she enjoyed to gamble, so perhaps husband and wife played together. Indeed, on Christmas Day 1502, she received 100 shillings for playing ‘cards this Christmas’, poignantly the last one she would celebrate.

For much of the festive period, the singing of carols (from the French carolle) could also be heard, often involving groups of people linking hands, moving in a large circle, with a lead singer stood within. The tradition of collectively singing carols at Christmas was already more than a century or two old by 1487, and could be sufficiently rowdy in content and practice they were usually prohibited from taking place on church grounds.

One of the more well-known fifteenth century carols was ‘the Boar’s Head Carol’, that celebrated the serving of such a head at the feast. This was first published in 1521 by the German printer Wynkyn de Worde, who practised his trade in England, and was probably sung when the head was carried into the royal presence, accompanied by the sounds of trumpets, lutes and much merriment.

Of course, sometimes the revelry could draw condemnation from observant churchmen. Of the Christmas celebrations of 1484, during the reign of Richard III, the Croyland chronicler disapprovingly recalled that ‘too much attention was paid to dancing and gaiety’. A bishop named Thomas Langton, who otherwise wrote approvingly of Richard, even noted that ‘sensual pleasure holds sway to an increasing extent’!

Christmas Day was not the first and last feast day of the Christmas period that needed to be navigated. The 26th was St Stephen’s Day, the 27th the feast of St John the Evangelist, and the 28th was the feast of the Holy Innocents, each with their own traditions and observances. The feast of the Holy Innocents, sometimes known as Childermas, marked King Herod’s decree in the Bible to slaughter all babies born within three days of Christmas, and traditionally this was commemorated with satirical role reversal. A Lord of Misrule was typically selected from the lower servant ranks to act as king for the evening, with many others reversing their roles so that household staff became lords and officers, taking great delight in mocking their social betters and ordering them about one night and one night only.

Although the custom would eventually be banned under the ever-precious Henry VIII, his father Henry VII was fond of the occasion, and although payments to a Lord of Misrule only appear in his household accounts from 1491, there is every possibility such a long-standing spectacle took place in some capacity during 1487.

On New Year’s Day, meanwhile, the traditional day of gift exchange in the Tudor court rather than Christmas Day like today, the royal family, their household and much of nobility congregated in Greenwich Palace’s Great Hall. King Henry, ‘being in a rich gown, dined in his chamber’, before ‘of his largesse’, or generosity to those around him, he oversaw the gift-giving ceremony. The principal recipients this year this year appear to be his Officers of Arms, though we do not possess his Chamber Books for 1487 to cross-reference.

In every year from 1498 to 1505, years we do have records for, Henry routinely seems to reward a host of his household staff, everyone from trumpeters, marshals, henchmen, pages porters, minstrels, the tumbler, an array of other servants and even a woman that brought him a cake. Most impressively, in 1503 the king paid £13 6s 8d to someone who brought him a leopard as a gift!

Back in 1487, the only reference we have in the Leland manuscript is that the king granted gifts to the value of £6, with the queen providing an additional 40 shillings, the king’s mother Lady Margaret Beaufort 20 shillings, and Jasper Tudor, the king’s uncle and duke of Bedford, also providing 40 shillings. This seems particularly low compared to later years so was most probably did not represent the full range of gift-giving. Others followed suit in giving monetary gifts of varying amounts, including the Duchess of Bedford Katherine Woodville, Bishop Foxe, the earls of Arundel, Oxford, Derby, Devon and Ormond, lords Welles and Strange, and the king’s Chamberlain, Sir William Stanley.

Thereafter, ‘on New Year’s Day at night there was a goodly disguising’, which meant dancing and entertainment whilst costumes and masks were worn to conceal the identities of those involved. Often, participants assumed the personas of heroes and villains, their masks sometimes those of the legendary figures they were portraying or even of animals and angels. It was reported that this particular Christmas, ‘there were many and divers plays’ put on for the enjoyment of all, accompanied with much wine consumption and laughter one imagines.

Christmas Day and New Year’s Day were two of the three big feasts of Tudor Christmastide. The third took place on Twelfth Night, or 5th January, to celebrate the Feast of the Epiphany the following day, the climax of the festivities. The evening before the feast, King Henry went to Evensong ‘in his surcoat outward, with tabard sleeves, the Cap of Estate on his head, and the hood about his shoulders’ – he must have appeared a wealthy and powerful spectacle. For this service, the king was the only person robed, with the religious duties handled by his close confidante John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury.

On the morning of 6th January, Henry rose early for Matins prayers, and on this occasion all nobility were likewise resplendent in their finest surcoats with hoods, following the crowned king and queen in procession. His mother, the proud Lady Margaret, through whom Henry inherited his claim to the throne, also bore ‘a rich coronal’ upon her head, whilst uncle Jasper was handed the honour of bearing the Cap of Estate before the king. Alongside him walked the earls of Derby and Nottingham, the earl of Derby, with the duke of Suffolk and one of the king’s closest confidante’s Giles Daubeney following close by.

John de Vere, the earl of Oxford and one of the Tudor heroes at the Battle of Bosworth, meanwhile, was afforded the honour of bearing the king’s train wherever he went, a privileged task for one who had done so much in placing then keeping Henry on the throne. Following thereafter including members of the royal household, including the Garter King of Arms, the King’s Secretary, and the King’s Treasurer, along with many other employees such as Officers of Arms, Heralds, Pursuivants and those of more menial positions such as carvers and cupbearers.

Once Mass was observed by all, King Henry returned to his chamber for a period, possibly to refresh and change clothes, before returning to the Great Hall, where ‘he was crowned with a rich crown of gold set with full many rich, precious stones’. Taking his seat ‘under a marvellous rich cloth of estate’, a rich textile canopy probably embroidered with his royal arms together with its supporters of the Welsh dragon and Richmond greyhound. Archbishop Morton sat on the king’s right hand side, and on his left, under her own cloth of estate that was slightly lower than his, was seated the crowned Queen Elizabeth.

Waiting on the king during the ensuing feast was again the earl of Oxford, whilst the earl of Ormond kneeled between the queen and Lady Margaret, the king’s mother. Sir David Owen, the king’s paternal uncle, acted as the king’s carver throughout the day. Owen was the illegitimate son of the king’s grandfather Owen Tudor, though was younger than his royal nephew. This David Owen had joined Henry in exile and had remained figuratively and literally close to his uncle in the early years of the latter’s kingship. A role as the king’s carver was no mean job, and highly sought after. Proximity to the king during state and religious occasions brought its own prominence in the eyes of the court.

Once the second course of food was completed, and after the minstrels had finished playing, the Officers of Arms descended from their stage and the Garter ‘gave the King thanks for his Largesse, and besought the King’s highness to owe thanks to the Queen for her Largesse’. Elsewhere in the Great Hall, in the middle was a table around which sat the dean and other churchmen associated with the King’s Chapel. After Henry had completed his first course, these ‘sang a Carol’, though sadly it isn’t recorded what carol it was.

On the right-hand side of the hall was another table headed by Jasper Tudor, who was seated alongside Giles Daubeney, the duke of Suffolk, the earls of Arundel, Nottingham and Huntingdon, the king’s half-uncle Viscount Welles, Viscount Lisle, and an array of other barons and knights. On the opposite side of the hall was another table, headed by the queen’s sister Lady Cecily, who was accompanied by the countesses of Oxford and Rivers and many other ladies and gentlewomen.

Another ancient tradition likely to have been observed on Twelfth Night, and possibly throughout the Christmas period, was wassailing. This involved the lord offering his guests a drink from a communal wooden cup, typically cider, beer or a warm spiced ale known as lambswool. Just seven years later, the act of wassailing was included in Henry VII’s household ordinances, detailing how:

“and as for the wassail, the Steward and the treasurer shall come forward with their staves in their hands, the King’s sewer and the Queen’s next, with their towels about their necks, and no man bear no dishes but such as be sworn for the mouth”.

It was further declared that “when the Steward come in at the hall door with the wassail, he must cry three times, wassail, wassail, wassail”. There seems little reason to doubt that this took place during the 1487 Christmas. After the year Henry had, he may have allowed himself a rare smile at this moment of great revelry among family and those few he trusted.

Once everyone had eaten, been merry and entertained to their hearts content, the end of the evening brought the Christmastide festivities of 1487-8 to a cheery close, a Merry Christmas having been had by one and all. The following morning, however, thoughts returned once more to the more tedious aspects of governing the realm, at least until the next holiday of note. Not unlike the modern day!

I do hope, like Henry VII back in 1487, you also are able to ‘keep your Christmas full honourably’, too!

Fantastic post Nathen! It’s been a real treat to be able to read in depth about what a Tudor Christmas was actually like.

Thanks for this post Nathen. It's very cool to be able to read such a detailed reconstruction of a specific Christmas from a historical household. Merry Christmas!