On 7 September 1497, a small flotilla of ships, perhaps as few as two, sailed into Whitesand Bay, Cornwall. Aboard were around a hundred souls, led by the shadowy figure of Perkin Warbeck. For most of the decade, Warbeck had claimed to be Richard of York, the younger of the missing Princes in the Tower presumed dead since 1483. He had succeeded in gaining some degree of recognition for his claim, but so far, within England, any success in pressing his claim had failed. Now, he was ready to finally lead a charge on London.

Leaving his Scottish wife Katherine Gordon behind in the parish of St Buryan, Warbeck and his small force headed north-east through the Cornish countryside, attracting some support from a local populace who had recently been destroyed during a tax rebellion against the king, Henry VII. The two Cornish leaders of that uprising, Michael Joseph and Thomas Flamank, had been executed, and many hundreds had been killed in battle at Blackheath. The Cornish, then, were only too prepared to support Warbeck’s plan to depose and kill the Tudor king, regardless of the veracity of his claim.

Part of Warbeck’s party was the implacable John Taylor, a native of Exeter who had been in the employ of first George, Duke of Clarence, and then Richard III. He was an avowed anti-Tudor rebel who had been at Warbeck’s side when the pretender first surfaced in Cork in the winter of 1491. Some (like me), suggest Warbeck’s entire impersonation can be laid at the feet of Taylor himself. Three of his captains, meanwhile, were named as John Heron, a debt-ridden former mercer of London, and two men named as Skelton and Astley.

Warbeck’s force first tried to rouse the tin miners, blacksmiths and farmers of Penzance, who ‘with one voice acclaimed him as their leader’. Three battle standards were raised – a red lion, a little boy emerging from a tomb, and a boy escaping the mouth of a wolf. By the time they reached Bodmin, it was said they had between 3-5,000 men, though a London-based chronicler dismissed them as ‘men of rascal’ who were for the most part ‘naked men’, that is, poorly armed.

At Bodmin, Warbeck issued a proclamation in which he called himself ‘King Richard IV’, second son of Edward IV. Pressing on, they headed across the moorland to Launceston, across the River Tamar on onwards towards the largest city in the region, Exeter

Now, Henry VII had discovered Warbeck had landed three days later, and urgently sent his agent Richard Empson to Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, with chests of gold to raise as many troops as possible. Courtenay was descended from a Lancastrian-aligned family who had been restored to his ancestral lands by Henry VII in 1485. He had fought for Henry at the battles of Bosworth and Stoke Field, and was created a Knight of the Garter. Interestingly, Courtenay was also the father-in-law of Catherine of York, a daughter of Edward IV who, if Warbeck was telling the truth, would have been his sister. Nevertheless, there doesn’t seem to have been any suspicion Courtenay would defect, which hardly paints Warbeck’s claim in good light.

Courtenay noted that Warbeck’s mainly Cornish force was considerable, and instead choose to retreat behind Exeter’s walls rather than chance a battle. The king had no issues with this, praising ‘his well-beloved cousin’ in a letter for having taken ‘so wise a direction’ since he wanted his city ‘surely kept’. Henry added ‘the chief thing we desire’ was for Warbeck to be ‘brought unto us alive’. To that end, he ordered Courtenay that once Warbeck’s army had left Exeter behind, he should follow with his men behind, so the ‘rebels and traitors’ would be trapped between his force and the king’s, which was on the way south. This way, Warbeck could be taken ‘without any stroke or peril’. Henry warned Courtenay to ‘follow our mind’.

Warbeck reached Exeter on 17 September around one o’clock in the afternoon. His attempts to persuade Courtenay to surrender the city unsurprisingly failed, and so the pretender ‘concentrated all his forces to break down the gates’. They even set some of them ablaze to try and force an entry. The following day, fresh attacks were launched on the gates, but in Courtenay’s words, the city was ‘well and truly defended’ in the name of Henry VII. There was an exchange of violence, however, with Courtenay himself injured by an arrow to the forearm, though he bragged that for every one of his men hurt, at least twenty of Warbeck’s were wounded in return.

By eleven o’clock in the morning on the second day of his siege, one chronicler noted Warbeck had lost about two hundred men and decided enough for enough. He gave the order for his men to withdraw, and to begin marching onwards to the next town of note, Taunton. By midday, Courtenay reported he lost sight of the rebels, before readying his weary troops to give chase as per the king’s commands.

On 19 September, Warbeck and his men reached Taunton, where he repeated his claims to be a son of Edward IV. He also offered coin money to all if they supported him. But Taunton was not a walled city, and offered no protection to the rebels. His plan to capture a stout fortress to establish as a headquarters had come and gone with the failed siege of Exeter, and now he was exposed. According to the later account of Polydore Vergil, Warbeck ‘did not put much trust in his army, the majority of his soldiers being armed only with swords, the rest of their bodies being unprotected’. They were, in short, men ‘completely unused to warfare’. These men also knew it, for they had started to desert Warbeck in their droves.

Everyone knew now that the king’s army was on its way, marching from Oxfordshire and into Somerset, reaching Glastonbury on the same day Warbeck reached Taunton some twenty miles away. Behind Warbeck was Courtenay’s Exeter forces, whilst the Baron Willoughby de Broke was charged with securing all ports. The trap was set, with Henry writing defiantly ‘we with our host shall not be far, with the mercy of our lord, for the final conclusion of the matter’.

On 20 September, ‘in the dead of the night’ and just three weeks since he had landed in Cornwall, Warbeck abandoned his army and tried to flee, evidence of his ‘feeble heart’ wrote Bernard Andre, a Tudor court poet. The perceptive Milanese ambassador, Raimondi, summed matters up in his report to the duke of Milan during this period, when he remarked:

‘Everything favours the king, especially an immense treasure, and because all the nobles of the realm know the royal wisdom and either fear him or bear him an extraordinary affection and not a man of any consideration joins the Duke of York’.

Hours before the pretender abandoned their army, Henry had likewise written from Woodstock to Oliver King, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, outlining his military strategy for ensnaring the pretender, confidently concluding his letter with the statement ‘We trust soon to hear good tidings of the said Perkin’. The king would not need to wait long.

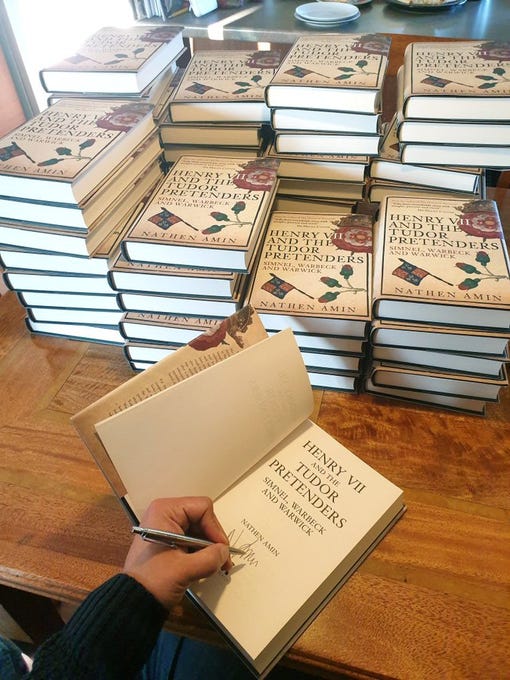

Henry VII and the Tudor Pretenders

Much of the above is an abridged version of that which appears in my book Henry VII and the Tudor Pretenders: Simnel, Warbeck and Warwick, which was the first book to cover the full rebellions which plagued Henry VII’s reign. To learn more about Perkin Warbeck, who he was, who he claimed to be, and what happened to him, check out my book. It’s a FASCINATING story.

I love that you focus on the importance of Courtenay in the defeat of Warbeck. Henry was so intelligent in the marriages of Elizabeth of York’s sisters, Cecily, Anne and Katherine, Bridget the youngest becoming a nun. I have a biography of the Tudor Earls of Devon written in 1961 which laughably states that the marriage of Princess Katherine and William Courtenay was a love match. Hardly. William’s dear old dad was a faithful Lancastrian exile and was knighted on Henry’s return. That marriage cemented that loyalty just as Cecily’s to John Welles half brother of Margaret Beaufort and Anne’s to Thomas Howard the future 3rd Duke of Norfolk. Henry’s strategies on the marriage market are part of why he succeeded so well with most of his aristocracy after he came to the throne.

A great read, Nathen. Thanks for sharing! I'm sure you've answered this question elsewhere (I've seen your face alongside Matt Lewis's!), but I'd be really interested to know your thoughts on the recent 'new evidence' uncovered about the princes in the tower... I found it difficult to believe its credibility, personally, but this era is far outside of my research area so I have only a shallow understanding of events!