'Medieval Women: In Their Own Words'

A review of the British Library's engrossing new exhibition

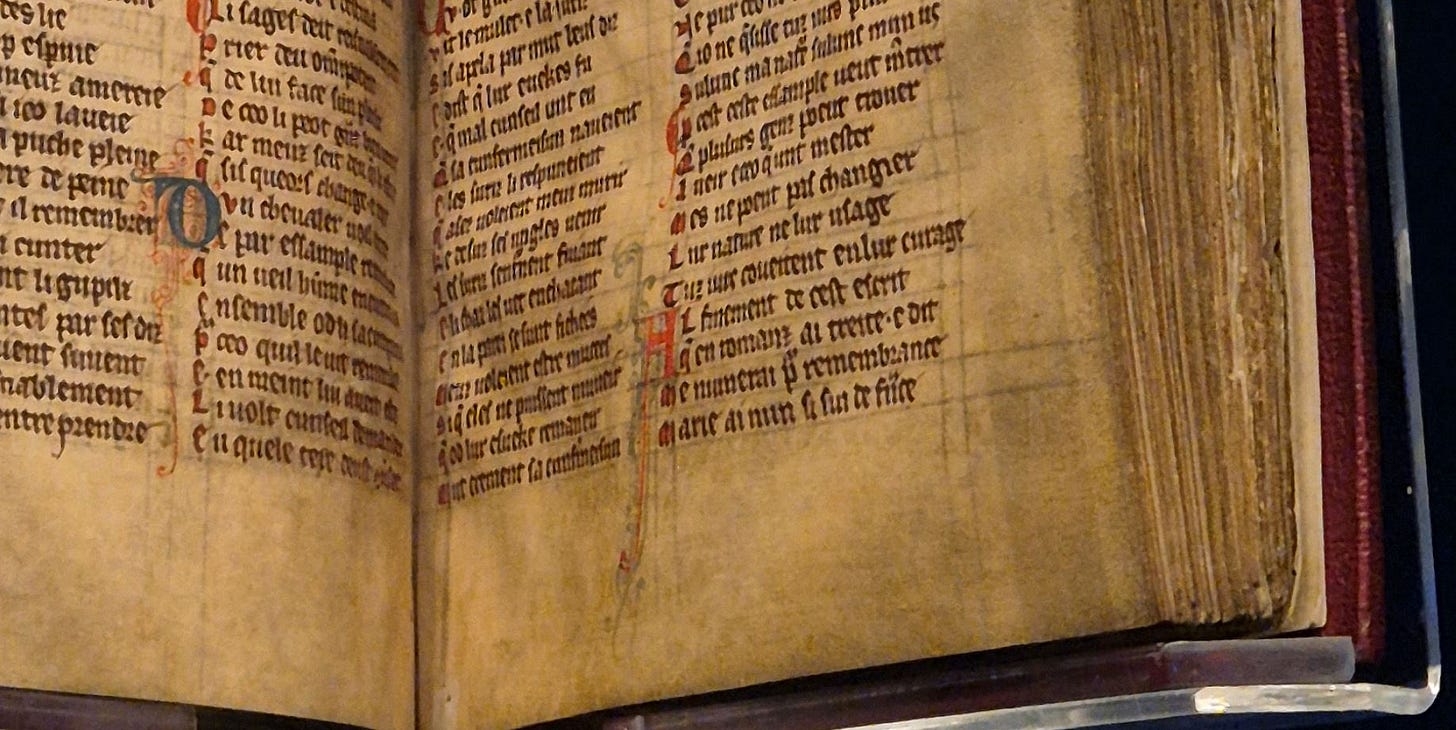

‘Marie is my name, and I am from France’

I had the great honour to be invited to a private viewing of the British Library’s incredible new exhibition, ‘Medieval Woman: In Their Own Words’, last night. And it was truly overwhelming in its scope.

The intention behind the new exhibition is to amplify the women of medieval yesteryear through their own words, visions and experiences, to free these famous and forgotten women from the traditional narratives that have sadly been long ingrained in our history. Since medieval women have often been excluded from our histories, their stories rarely recorded for posterity, this is a ground-breaking project in every way.

I spoke to the curatorial team, Eleanor Jackson, Julian Harrison, and Calum Cockburn, who collectively explained how it took more than two years to conceive, plan and construct this exhibition, which involved thousands of hours of research to put everything together. In total, they were able to bring together more than 140 manuscripts, documents and artefacts to illuminate the vibrant if complex lives the medieval woman, regardless of rank, led. Crucially, this story is told through their own words, and not those of the men that shaped the world they lived and how they have all too often been remembered. It’s an extraordinary achievement.

Upon descending the stairs into the exhibition area and past a statue of Eleanor of Castile, queen of England, the treasures of yesteryear come thick and fast. Navigating through the displays, each not only beautifully exhibited but accompanied by detailed descriptions so we understand the importance of the object and the woman associated with it, I think on at least a few occasions I gasped when it became clear what my eyes were looking upon.

Christine de Pizan & Margery Kempe

Personal highlights for me were many. The works of Christine de Pizan will undoubtedly prove popular. When Christine was widowed, in order to support her two children, she turned to writing, eventually winning the patronage of the French royal family and the leading aristocrats of her day. A prolific writer, she typically defended the moral and intellectual character of her fellow women, and is rightly regarded as the first professional female author. In the exhibition, richly decorated manuscript, ‘The Book of the Queen’, is beautifully presented, opened to the page where she is depicted presenting the book to Isabeau of Bavaria, queen of France.

As Pizan herself wrote, "God has given women such beautiful minds to apply themselves, if they want to, in any of the fields where glorious and excellent men are active" – the exhibition is the perfect demonstration of that his concept was, indeed, accurate.

We also see an elegant Book of Hours that once belonged to Joanna I, Queen of Castile, that shows her kneeling before the Virgin Mary, and the famous ‘Valentine’ letter, sent in February 1477 from Margery Brews to her ‘well-beloved Valentine’, John Paston III. One of the earliest texts on display is the Psalter of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, dating from 1131-43. Written in Latin, the Psalter nevertheless is illustrated in the Eastern Christian style bearing Greek inscriptions, appropriate for a queen who was notable for her patronage of both eastern and western Christian traditions.

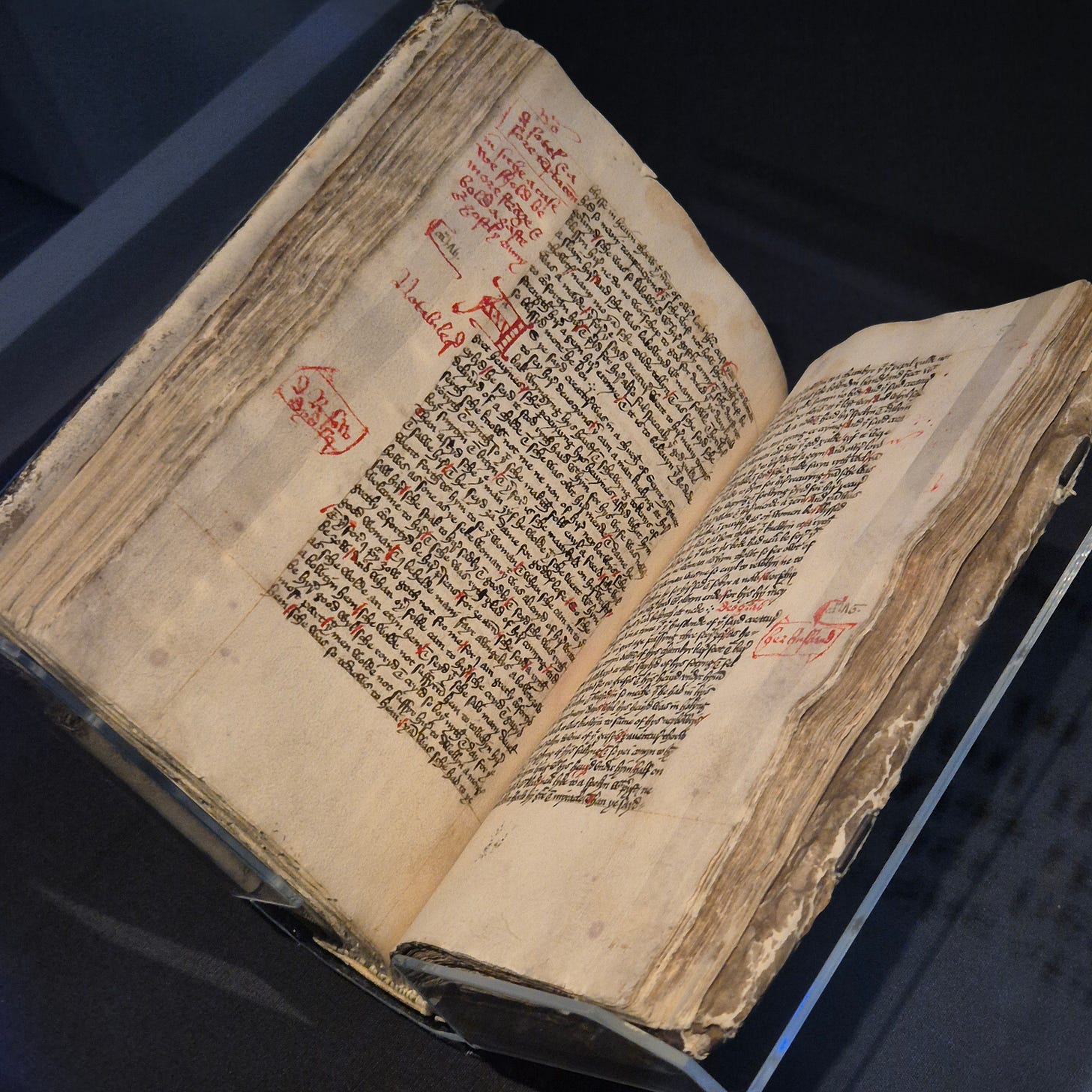

Having written about Margery Kempe in my book ‘The House of Beaufort’, it was also particularly thrilling to look at the only surviving manuscript of ‘The Book of Margary Kempe’. An East Anglian mystic often accused of heresy for her visions, Margery was keen to record her life story, which she dictated to a priest, explaining in excruciating detail her lengthy struggle for recognition in a male-dominated religious world. The result is regarded as the earliest autobiographical account in English, but what is astonishing is that we may never have heard Margery’s voice if not for a chance discovery in 1934. In a Chesterfield county home, someone went looking for ping-pong balls in the back of a cupboard, and instead found a leather-bound clutter that proved to have huge historical importance, salvaged after the Reformation and then since forgotten. A remarkable treasure.

The Pastons naturally feature heavily – every medievalist is aware of the extraordinary legacy they bequeathed to us through their surviving writings, and this includes the matriarch of the family, ‘God’s own gentlewoman’ Margaret Paston, whose personal correspondence and will is featured.

Elizabeth Woodville, Margaret Beaufort and the Gender Pay Gap

In 1483, two women, Elizabeth Woodville and Margaret Beaufort, combined to try and bring down the king, Richard III. It was their conspiring which helped bring into being the alliance that would topple that king two years later, with their children, Elizabeth of York and Henry Tudor, marrying to unite the warring houses of York and Lancaster. It is appropriate both feature here. There is an image of a striking Elizabeth Woodville staring out at the observer, depicting in the 1475 Book of the Fraternity of the Assumption of Our Lady, whilst Margaret’s 1505 indenture book is on display, a page proudly bearing her coat of arms, her heraldic devices including red roses of Lancaster and the Beaufort portcullis, and a smattering of Margeurite flowers, referring to her name.

Lower down the social scale, meanwhile, is a fascinating 1483-84 account roll, taken from the manor of Stebbing in Essex. Looking closely at the information contained, it records that 27 men and 16 women were hired that summer to bring in the harvest, with the men being compensated 4p a day and the women 3p. It would seem the gender pay gap existed 500 years ago!

Monkeys and Lions

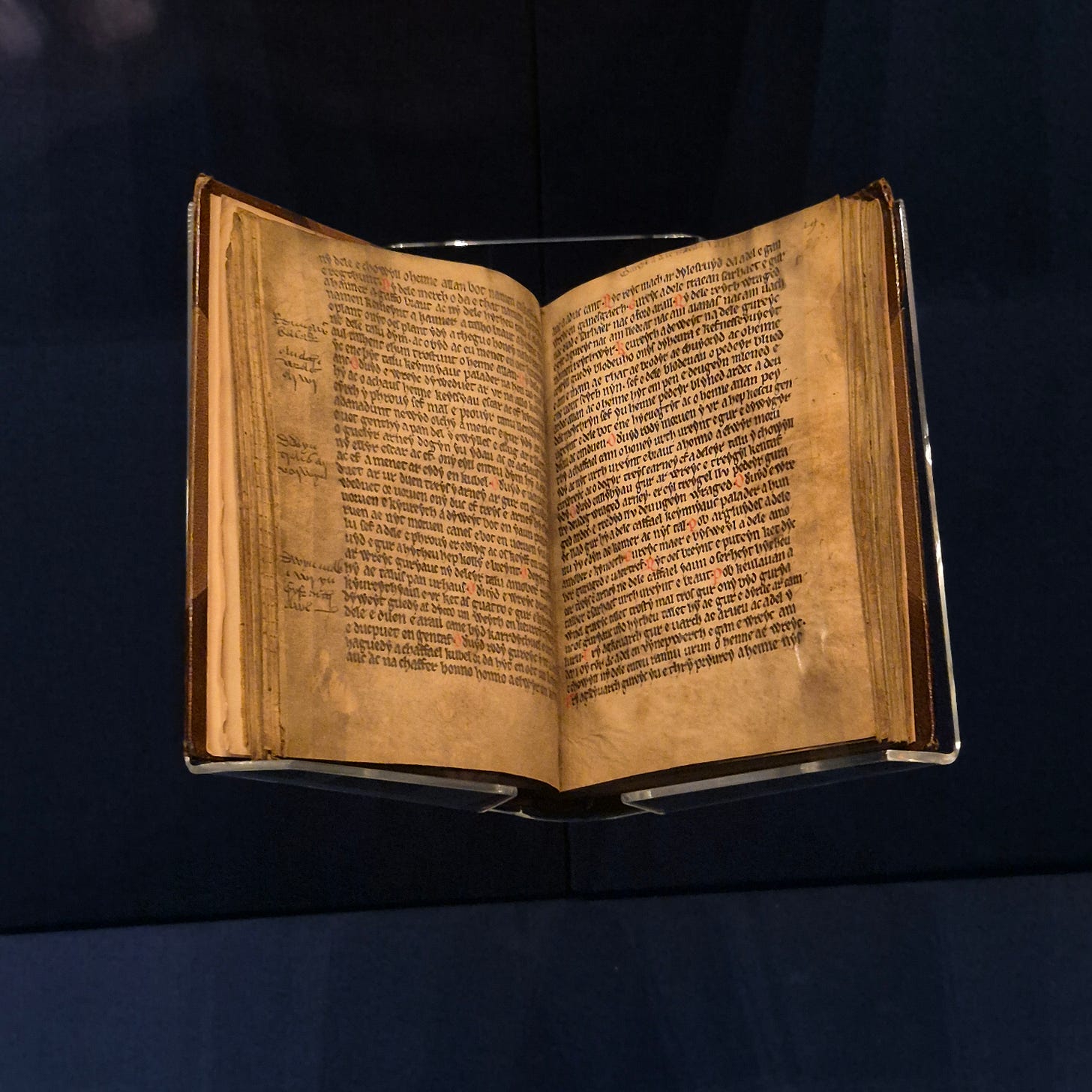

Being Welsh, I was naturally drawn towards two Welsh works of note. One, the Llyfr Iorwerth, is a 13th century Welsh lawcode that explains how a woman could divorce her husband under Welsh law. She was permitted to leave her husband within seven years of their marriage on one of three grounds - if he had leprosy, if he was unable to have sex, or if his breath stank! If this was proven, the woman would retain all her rights and possessions in divorce.

There is also a Welsh language poem dating from the reign of the Welsh-born king of England, Henry VII, which explains how Annes, abbess of Llanllyr, had commissioned a bard named Huw Cae Llwyd to perform for a knight, in the hope he would grant her one wish - a pet monkey! Sadly, we don't know if Annes got her mwnci!

The artefacts on display aren’t to be ignored, either. Two caught my eye – one, a barbary lion skull that was uncovered in the Tower of London moat in the 1930s and dated to the 15th century. We know from account books that Margaret of Anjou, queen of England, had been gifted a lion and that it was kept in the Tower’s menagerie? Was this the queen’s pet lion?

There is also a resplendent 15th century Foundress’ Cup, a silver-gilt vessel bearing the entwined coat of arms of Eleanor Cobham and her husband Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. Eleanor was a controversial figure in her day, and in 1441 was forced to divorce her royal husband, stripped of her titles and possessions, and made to perform public penance after being tried and convicted of committing treason by consulting astrologers, a woman who had fallen victim to the politics of men. For her alleged crime, she was imprisoned for life. She would die a captive. The cup later passed to Lady Margaret Beaufort, matriarch of the Tudor dynasty, who bequeathed it to Christ’s College, Cambridge.

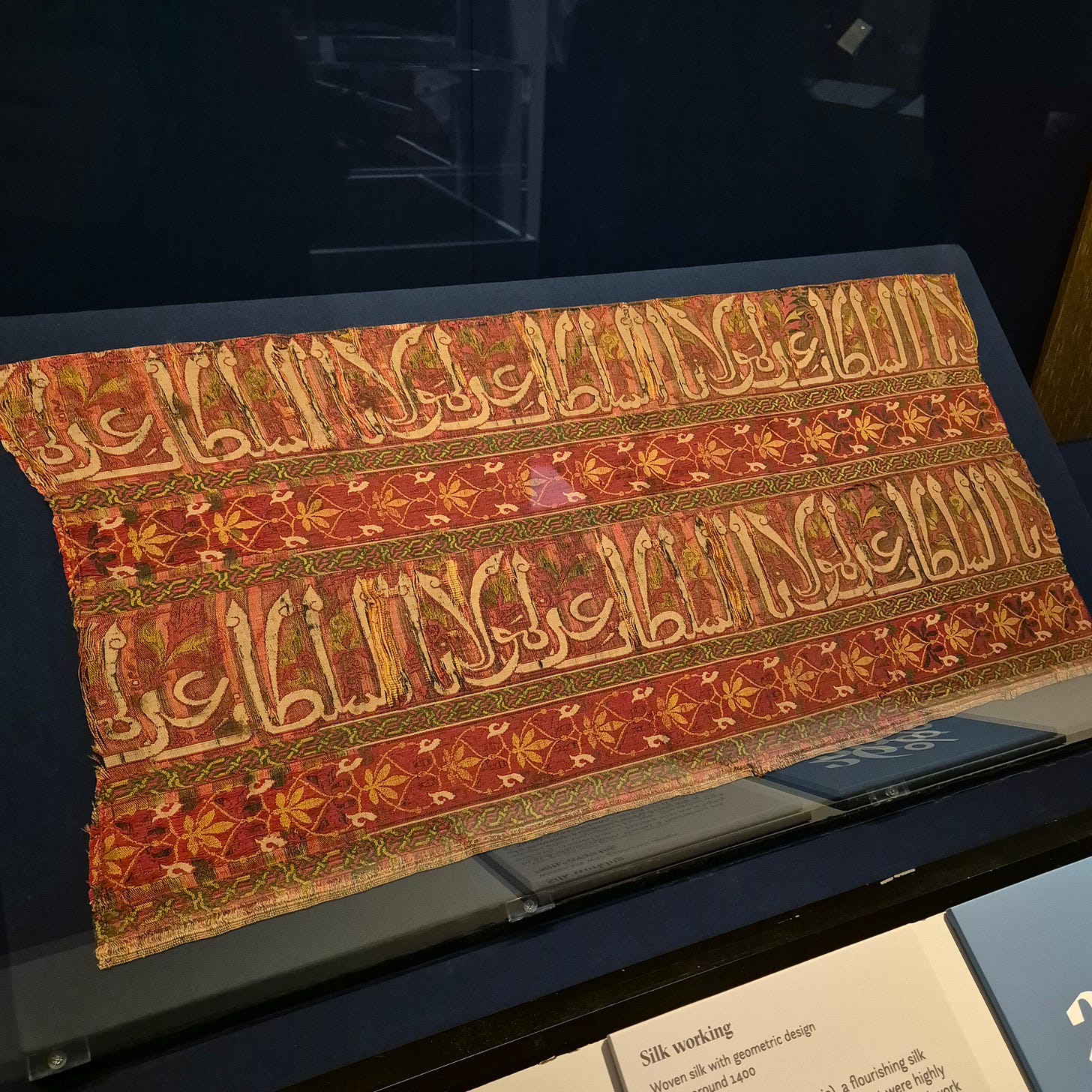

Having recently visited Granada, it was also inspiring to see a remarkable silk textile made in Islamic Spain by an unidentified Muslim woman. The silk, a beautiful red affair with intricate geometric design, bears the Arabic inscription ‘Glory to our Lord the Sultan’, variations of which can still be seen inscribed around Moorish palaces across Andalucia, the successor to the Muslim Iberian kingdom Al-Andalus. The fall of Muslim Spain was a violent and troubled period in European history, and this silk, carefully crafted, hints at a lost world.

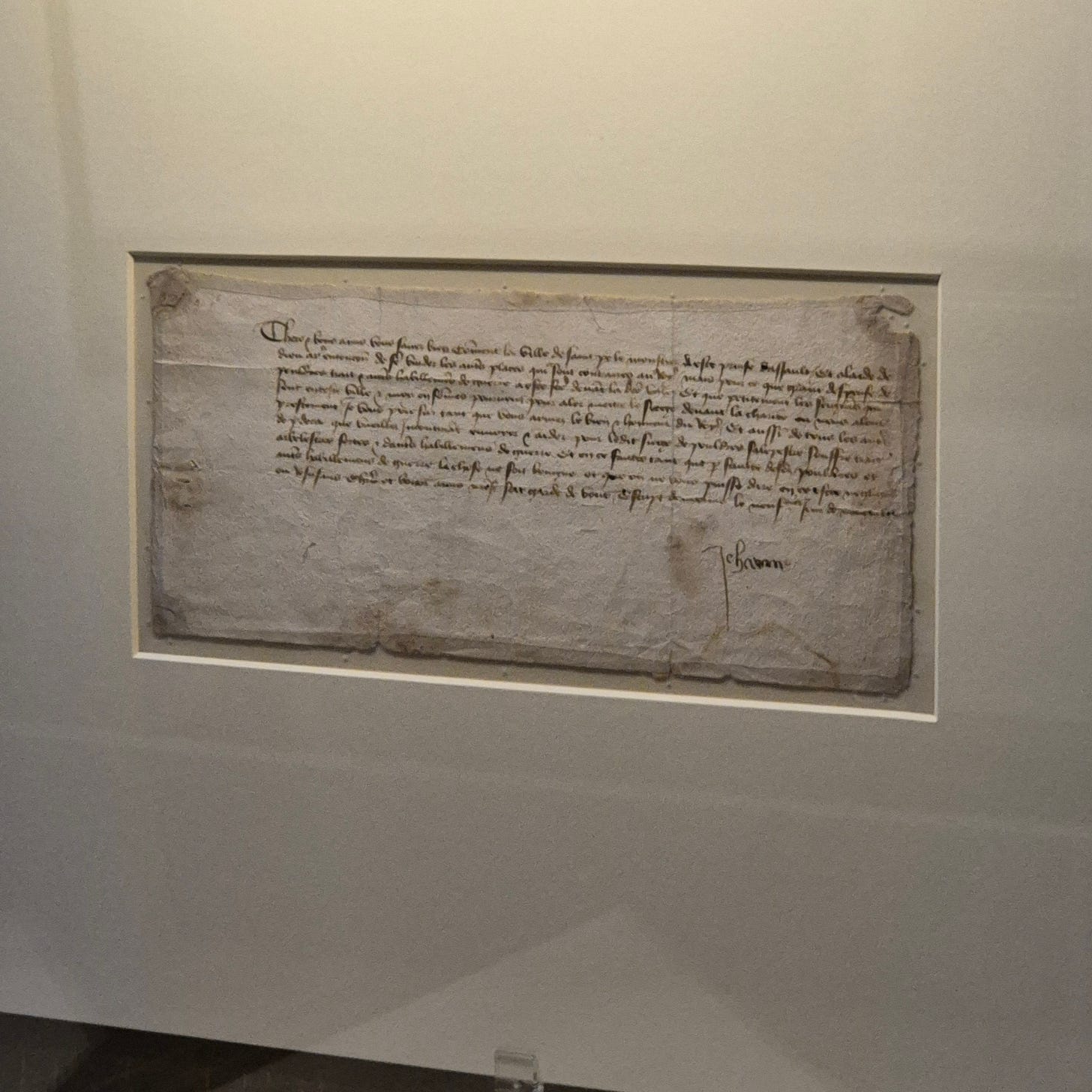

Jehann

The star of the show, though, is undoubtedly Joan of Arc. For the first time ever outside the French town of Riom, a letter bearing Joan’s own signature is on display. On 9 November 1429, Joan (or Jehann as she would sign herself), wrote to the citizens of Riom imploring them to send gunpowder, arrows, and other military equipment so she could besiege the town of La-Charité-sur-Loire in the name of the French king. Since Joan could not read nor write, she dictated the letter to scribe, but it does seem she was trained to sign her name, having previously used an X. Seeing her name up close, her unsteady hand clear, is an emotional experience, knowing her fate would be to die for daring to step forward and challenge medieval societal norms.

Finally, we encounter the mysterious woman whose quote I chose to open this article with, a 12th century Frenchwoman known only as Marie de France. A poet of considerable talent, Marie wrote stories of magic, romance and chivalry, and was successful in her own day, her work being translated into many languages. She explored themes such as gender relations, sexuality, romance and nobility, and may even have inspired some of the stories that feature in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

In one of her works, the one on display, she finishes with the line ‘Marie ai nun, si sui de France’ – thanks to this, we know her name, the earliest recorded instance a female poet is identifiable by name. We can pay tribute to her all these centuries later. She, and every woman featured in this absorbing exhibition, deserve nothing less.

‘Medieval Woman: In Their Own Words’ is running at the British Library, London, between 25/10/2024 and 02/03/2025. Tickets are available on the British Library website.

This is so exciting! I’ve written a book with OUP (A Hidden Wisdom: Self-Knowledge, Reason, Love, Persons, and Immortality) that looks at the philosophical aspect of writings of medieval women like Hadewijch, Marguerite Porete, Catherine of Siena, and Julian of Norwich’s, and I love that the contributions of medieval women are increasingly getting their due - and in their own words!

Re: Joan of Arc: dozens of eyewitnesses said she was executed by a pro-English tribunal because she had opposed the English government, not for the reason this article claims ("daring to step forward and challenge medieval societal norms") since she didn't do that: she denied fighting or calling herself a commander, confirmed by numerous eyewitness accounts, and she had already been previously approved by high-ranking clergy at Poitiers in April 1429 (after Charles VII had her examined for orthodoxy) which included the Inquisitor for Southern France. She was a religious visionary in an era when many women and girls had been accepted in that role, so her role did not violate societal norms. The English also executed a boy named Guillaume le Berger for opposing them, so it had nothing to do with gender. Additionally, her signature is "Jehanne" rather than "Jehann" as this article says: if you look closely you can see an 'e' at the end, which is clearler in her other two signatures on other letters. If anyone wants to see the full translation of the letter in the exhibit, here's an online translation : https://archive.joan-of-arc.org/joanofarc_letter_Nov1429.html

That site also has translations of all of her other surviving letters: https://archive.joan-of-arc.org/joanofarc_letters.html